The seventh graders sat together in pods of two. It was time for Ms. Yarrell to work them through their thought exercise on the least common multiple.

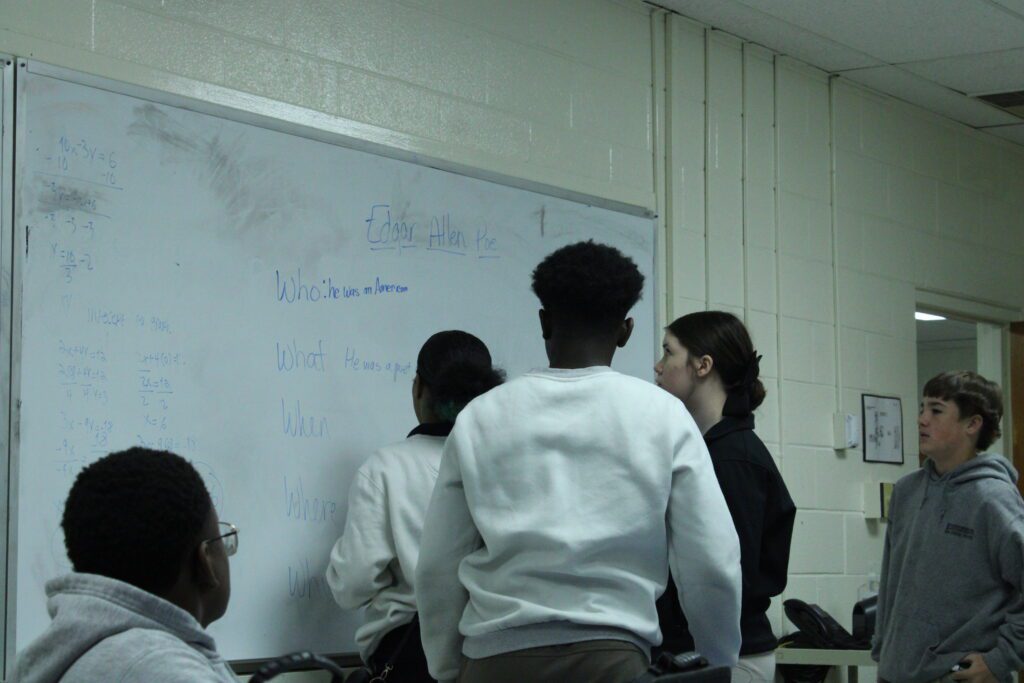

Visitors from the Teach for America program watched them scribble on their desks with whiteboard tops. Yarrell walked the visitors through how they rotated sitting in different pods to work on their collaboration skills and how instead of telling the students their answer is incorrect, she would say “I disagree.” She gives students the opportunity to talk through their answer and discover why it’s wrong, instead of shooting them down.

This was one of many stops in the group’s tour of West Edgecombe Middle School. The school is a Teach for America partner, and the visitors were TFA members who were passionate about being educators in rural settings like eastern North Carolina. Small efforts like seat assignments and larger efforts like community partnerships have helped the school reach for the district’s goals.

One district level goal is retaining teachers. At West Edgecombe Middle School, Principal Kelsey Ballard said they have been able to retain math and English language arts teachers. However, they have struggled with retaining science and social studies teachers, she said, due to licensure requirements.

There has been a rise teachers across the state over the past two school years. Ballard said due to state laws, when teachers that they hire do not make enough progress on getting more credentials in a two or three year period, they have to part ways. That makes retention in those subjects difficult.

Notice: JavaScript is required for this content.

Ballard said some people who graduate with teaching degrees have a dual license in two subject areas — but that is not always the case. Not having as much flexibility to move teachers between subjects really ties her hands, the principal said.

“And so we lose a decent amount of folks. (They) come and work for two or three years, and then at the end of that time, when they haven’t met the requirements for the state licensure, we have to part ways, and there is nothing we can do,” Ballard said.

A long with having trained teachers in the classroom, district leaders said how rigorous the instruction is matters.

Michael Myrick, deputy superintendent and chief academic officer for Edgecombe County Public Schools, said that they are striving to make sure students are able to get the help they need while still being exposed to grade-level standards.

“We want to get all of our schools at least 10% increase in every area. We don’t feel like we should have any schools that are low, because we should be able to exceed appropriately, because of where our students are,” Myrick said.

At West Edgecombe Middle School, students get assigned to class periods where their teachers can track their progress with the i-Ready diagnostic platform, catch up on assignments, or go to classes like HELPS reading intervention.

In HELPS, students work on their reading fluency and then once they advance through that, they read different texts as a group to help close the comprehension gap. The teacher works with only a handful of middle schoolers at a time. Students said that being in a smaller group makes them feel more comfortable reading out loud compared to when they are in their larger classes.

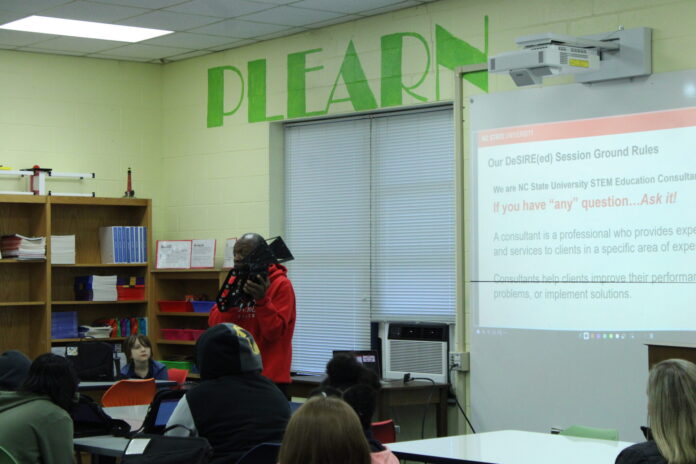

West Edgecombe Middle also has students particularly engaged in STEM. Along with a core science class, students get to participate in Developing STEM Identities in Rural Audiences through Community-based Engineering Design, also referred to as Project DeSIRE. The partnership with North Carolina State University is designed to help students explore their interests and career possibilities in the field.

Students take Project DeSIRE as an elective, but each cohort works on a different skill. The current seventh grade class is focused on advanced manufacturing. Students are split into teams to figure out how to design, build, and market a beach shore sweeper robot.

Representatives from N.C. State visit the school to serve as “consultants” for students while they complete their project.

“You know, colleges want to help because they’re helping their future enrollment. Businesses want to help because they’re getting their future employees. And so just not being afraid to ask for those partnerships is what’s really pivotal for us here,” Timothy O’Shea, head of family engagement and academic support at West Edgecombe Middle, said.

At the district level, Myrick said opportunities for partnerships and grants could be seen as an advantage of being in a rural district. However, the deputy superintendent said that the resources have to be weighed against their other priorities.

“Sometimes we get so caught in being innovative and creative. Sometimes we forget that, you know, there are certain things that still have to happen at the same time, like teaching kids how to read, teaching kids how to do math, those kinds of things,” Myrick said.

Another look at Edgecombe County Public Schools

Another perspective on change within the school district is that of the community and of the parents.

Samantha Dale is a manager of leadership development for Teach for America. In addition to this role, she has children in the Edgecombe County Public Schools district.

Dale said that schools that are trying different things, like project-based learning in STEM and microschools. These are things she wants her children exposed to and are different compared to the time she was in school.

“But as a parent, I also want them to be able to socialize and have conversations with people, problem solve, because everything you cannot find on the Google. And that is the gap, I think, that sometimes gets replaced with technology — that they’re going to have to be able to build that social gap,” Dale said.

An example of a way to fill a social gap is the social-emotional learning (SEL) elective West Edgecombe offers. A small group of students works with a guidance counselor for a class period to work through managing conflict and other things that may be going on in their lives.

Edgecombe’s educators said that the small “hometown feel” of their environment can be leveraged to build strong community connections in a rural area to support innovation, rather than seeing the rural context as a disadvantage.

Brandon Lam, who runs the nonprofit Versademics in eastern North Carolina, said he always polls parents when they are considering a new initiative, and they sometimes bring up points that their organization overlooks.

“I think people are more willing to let you take a risk if they know that it is for the kids when you try to innovate,” Lam said. “Especially in my space, when I try to innovate, I want to make sure that it’s something that my community actually wants.”

Editor’s note: Dr. Monique Perry Graves, executive director of Teach for America North Carolina, is a member EdNC’s board of directors.