School leaders, organizations and governments are sounding the alarm about chronically absent young people, typically defined as those who miss 10% or more of the school year whether due to excused or unexcused absences. Research has long demonstrated that chronic absenteeism is correlated with “increased rates of high school dropout, adverse health outcomes and poverty in adulthood, and an increased likelihood of interacting with the criminal justice system.” While chronic absenteeism has been rising nationwide before 2019, after COVID, rates as much as doubled in multiple states.

In August and September of 2024, we interviewed 30+ young people, principals, teachers, entrepreneurs, policy analysts and researchers from across the country to better understand the causes of chronic absenteeism. Since then, another 90+ people have reviewed our findings and tested our ideas through interactive workshops. What we found convinced us that the term itself may be limiting our ability to look at — and address — the different causes of youth absenteeism.

Notice: JavaScript is required for this content.

Introducing the new absenteeism

Researchers Hedy N. Chang and Mariajosé Romero first recommended the language of “chronic absence” in a 2008 report about low-income elementary schoolers, and Chang went on to launch the nonprofit Attendance Works in 2010. This jumpstarted important work addressing and preventing chronic absences, and the 2015 federal education law Every Student Succeeds Act became the first to require states to track and report chronic absenteeism. Since then, researchers and practitioners have emphasized the importance of understanding different root causes when tackling the issue.

The stories we heard made us consider whether we can even rely on a single term to describe a broad swath of young people’s experiences, and have convinced us that we need to revisit the phrase in order to effectively track and address these issues. In particular, the experiences of some groups of young people, echoed throughout our interviews, are not well represented in existing conversations:

- Young people who know that learning is valuable and are doing it outside of a formal classroom setting. They are marked absent but may be engaged through employment or community involvement.

- Young people who are present in school but disengaged mentally. While they aren’t getting counted as absent, they have a lot in common with the group above.

- Young people who are experiencing such extreme circumstances and distress, for whom showing up at school feels nearly impossible to prioritize.

We are introducing the language of the new absenteeism to describe these young people and others like them. In this article, we introduce five profiles of attendance and engagement using examples and quotes from our interviews. The visual in the next section considers both physical and mental presence in schools: whether young people are there and whether they want to be there.

From what we’ve gathered, young people are disconnecting from school in fundamentally different ways than they were 15 years ago — we’ll explore some possible reasons below. Our hope is to encourage school leaders and their champions to imagine new ways to tackle what absenteeism actually looks like today.

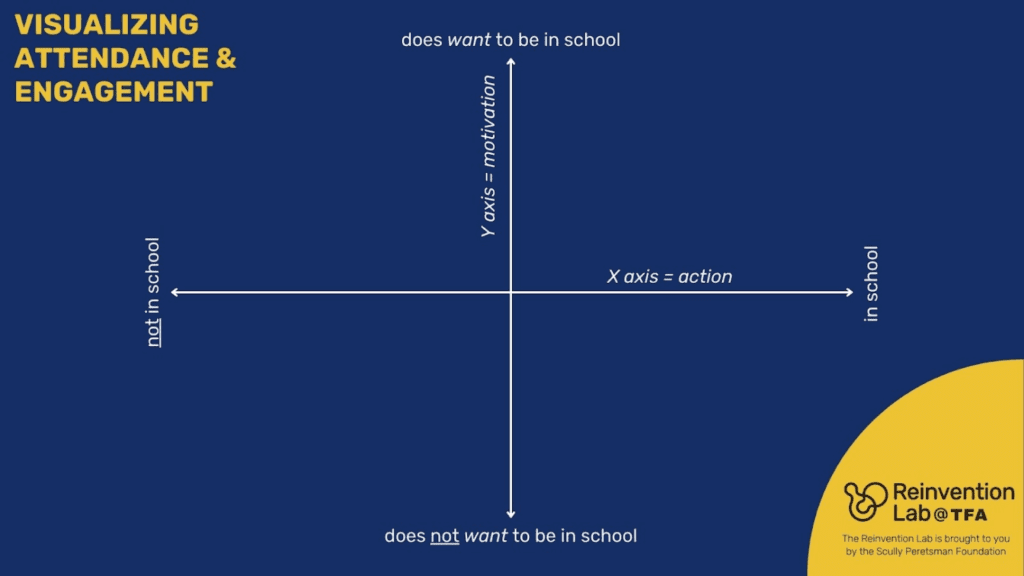

Visualizing five profiles of attendance and engagement

In the visual below, the X axis reflects the young person’s action: whether they are physically present in school or not. The Y axis reflects their motivation: whether or not they want to be in school.

Using these axes, we are able to define five profiles of attendance and engagement.

The first two profiles are “above the line,” indicating that a young person has the motivation to be in school, whether they are able to attend or not.

Engaged: “I’m doing just fine.”

This group is generally engaged in school, showing up, doing their best, and authentically invested in their education. They both want to be in school and are in school. For the purposes of our work, we think of these young people as the “control group” — not chronically absent.

Systemically Blocked: “I know school’s important, but life happens.”

This group is what most adults focus on when they think of chronic absence. These young people want to be in school but are not in school. They understand that education is important but are struggling with complex issues that get in the way. Homelessness or precarious housing, lack of access to transportation, or other competing priorities (like a part-time job or dependents) all wrestle for attention.

Other themes named by interviewees include: safety concerns, illness, caring for family, exclusionary discipline, and inclement weather.

“So partway through the month…between paychecks…there are families who don’t have money to go to the laundromat. And so they don’t send their kids to school because they don’t have clean clothes and schools have addressed that by adding…washers and dryers into the school that families can come in.”

— Leader from nationwide organization that supports schools in absenteeism solutions

The next three profiles describe young people who are not motivated to be in school, whether they’re actually attending or not. We describe these “below the line” profiles as the New Absenteeism.

Real-life Learner: “I’m doing something different.”

These young people aren’t in class and don’t see school as valuable, but they are not rejecting education overall. They’re pursuing alternatives that feel more meaningful to them, like entrepreneurial ventures, work-based learning, apprenticeships, or self-directed projects. They may feel that their school environment and pedagogical approaches don’t recognize their path to growth or help them succeed. For some, speaking up hasn’t changed the system, so they’ve created their own way forward outside of school.

Other themes named by interviewees include: a young person’s learning style not being accommodated in school, classes and tests lacking relevancy to life, teacher vacancies and shortages, and unengaging course materials.

“They are in community, like they’re drinking coffee at the Ghanaian coffee shop and learning all about Ghana, and then they’re going over to this auto body shop and building a car…and they’re gonna be around people who are also showing up as themselves… What if we really are all teaching each other? … In other places, I’m seeing it work well — it’s based on breaking down the education and life barrier. So then, kids are able to swim between more easily.”

— Executive Director/Co-Founder of an alternative program

Checked Out: “I’m here, but what’s the point?”

These are young people who, according to all official measures, are in school. They’re showing up and their names are being checked off the attendance list. But mentally, they’re not there. They may be attending regularly because their families have mandated it or because they don’t see an alternative. Their hearts and minds aren’t there, and their peers and teachers can tell.

Other themes named by interviewees include: bullying or other harmful school dynamics, struggles with attention and distraction, lacking a sense of belonging, and encountering challenging coursework without additional support.

“What I’ve seen [since the pandemic] is a lack of engagement. … I’m like, this is the only time I have with you, set your cell phone aside. … For the most part when [students are] with me, they’re engaged, but overall, education doesn’t have the same impact that I feel like it used to where people want it. … The buy-in isn’t there, the connection.”

— New York State public school teacher

In Crisis: “I’m done.”

These young people are sapped of the motivation or ability to show up for the basic necessities of life, let alone school. They may have critically unmet resource needs in their families or be experiencing abuse, trauma or justice system proceedings. They are pessimistic about the power of schools and educators to help them. The depth of their challenges, and in many cases their distrust of the education system, sets them apart from the other profiles.

Other themes named by interviewees include: life-threatening health issues, prolonged family chaos, abuse from former school staff or grief.

“I have depression. I have anxiety and stuff. And so sometimes it’s really difficult to, um, you know, get to school in the mornings or even sometimes stay for the whole day. Like I know this morning I was maybe having an anxiety attack. It’s easier to stay at home than having to go through that while feeling that sense of nothingness, I guess. It’s just hard to go to school and having to do all this stuff when you don’t even feel like really existing at that moment, you know?”

— High school senior in California

As you reflect on this framework overall, here are some questions to consider:

- Does this visual framework resonate?

- Have you encountered these profiles of attendance and engagement?

- Can you map your student body according to the visual? How would you identify where young people are at?

- Do you see a rise in the New Absenteeism? Do the Real-life Learner, Checked Out, or In Crisis profiles describe the majority of the young people you work with?

- What approaches have you seen be effective for each profile?

- How could you reallocate resources that work for these profiles of young people?

- What surfaces when you share this with colleagues?

Implications of the New Absenteeism

Existing efforts tend to focus on Systemically Blocked young people

In our research, we began to see that most existing efforts to address chronic absenteeism are tailored to the Systemically Blocked profile. Many of these approaches (e.g., creative transportation solutions, the blending of social support systems with the education system) have been tested over years, if not decades, and have proven their value in addressing that kind of absenteeism. But what about the New Absenteeism, the youth who are “below the line”? For these young people, we are still early in our collective understanding of what really works and why.

These profiles require distinct attention and intervention

“Every single person is living life, and life is a chaotic thing and has a lot of different factors and a lot of things intermix. … Usually one issue comes with another issue, comes with another issue.”

— High school senior in California

The term “chronic absenteeism” groups together so many different youth experiences that it becomes too broad to be useful, especially given the changes wrought by the COVID pandemic. School leaders across the country are increasingly confronting these new profiles of absenteeism, yet our systems remain calibrated to address yesterday’s challenges.

These profiles are also fluid: Young people can move in and out of them over their years in school and even within the same school day. The important thing is having targeted intervention strategies for all the youth profiles — with a special emphasis on what’s troubling your own community most and could effectively re-engage young people.

Young people increasingly see themselves “below the line”

Across the 41 young people who engaged with our findings, 56% chose Real-life Learner when asked to pick the persona that most “speaks to them” or that “felt most resonant,” while 44% chose Checked Out. This included even youth who previously identified themselves as Engaged (e.g., non-absent) or Systemically Blocked. The New Absenteeism represents a growing disconnect between our educational system and the young people it aims to serve.

Young people are increasingly questioning the value of the formal school system and beginning to think of it as optional. For many, the place of school in their lives is no longer as central and obvious as it was for previous generations. What are possible reasons the New Absenteeism resonates with so many young people’s experiences? We have a few hypotheses:

- Young people treating school as optional, similar to in-person work for adults post-COVID

- Teacher shortages and turnover (an adult absenteeism crisis!)

- Growing unmet mental health needs and self-reported “cognitive overload” since the pandemic, among both youth and adults

- Both young people and families reporting public schools as decreasingly relevant

- Microschools and alternative schools gaining popularity and accessibility

Reflections and reactions

Between September 2024 and February 2025, 90+ people engaged with our findings through design workshops and conversations. Overall, participants shared that our focus on “below the line” profiles was refreshing and different from typical research that concentrates on Systemically Blocked young people.

Some questions came up, which point to areas for future inquiry:

- How can schools begin to effectively measure and track the Checked Out profile?

- Are shifts in youth attendance and engagement permanent or a result of lingering COVID impacts?

- How can we combat defeatist attitudes about chronic absenteeism?

- Are there case studies demonstrating the effectiveness of specific interventions into the New Absenteeism?

- How sustainable are alternative education models like microschools?

- Can local organizational partners (e.g., museums) be leveraged to address the New Absenteeism?

We know there are school and district leaders, educators, and organizations working tirelessly to intervene in and prevent the New Absenteeism, some of whom we got to speak with. We welcome examples of model programs and initiatives. Many participants shared examples of nascent solutions and amazing efforts that pay close attention to young people living “below the line.” There is a lot to be optimistic about as we investigate and address the New Absenteeism.

We hope you’ll test the resonance of our thinking against your own experiences, challenge its assumptions, and use it to start conversations.

Additional support in this work came from: Elisabeth Booze, Tanya Paperny, Sunanna Chand, Oluchi Igbokwe, Seth Trudeau, Samantha Asante-Bio, Izzy Fitzgerald, and Sydney Tweedley.

The Reinvention Lab is brought to you by the Scully Peretsman Foundation.