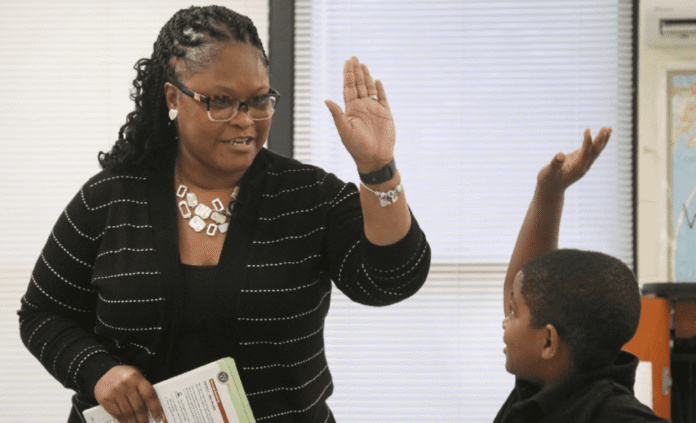

During much of the morning, reading class almost feels like a well-choreographed TV game show. Resting on a counter next to the huge video screen there’s a timer that gently ticks away and occasionally dings to keep each segment moving. Images, often full sentences in large type, flash across the screen while second-grade teacher Jacquelyn Boyd asks questions about what they’re reading. Around the studio — uh, make that the classroom — hands shoot into the air, not only to give an answer, but also to help students figure those answers out.

One teaching technique called “finger stretching” helps everyone sort through individual sounds in a word they don’t know yet, and a half-dozen specific hand gestures show how the letters in each syllable make a particular sound. A closed fist means a closed syllable. (Those are syllables where vowels are “closed off” by a consonant at the end. In those words — take “dog” for example — the vowel “o” is pronounced with its short sound.) The two-finger “peace sign” means there’s a long vowel sound in the syllable with a silent “e.” An open hand means an open syllable. And there are more.

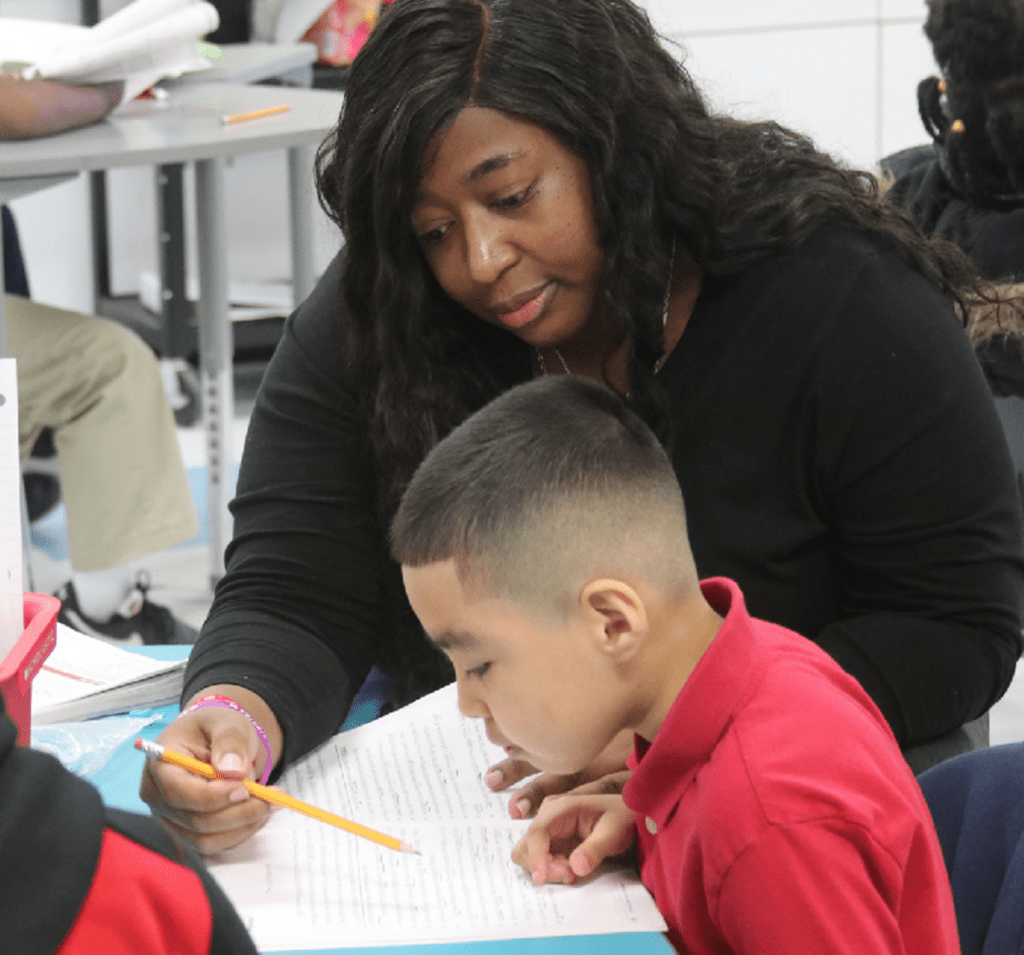

After a while, class shifts to something very different. Now, students are reading passages in their books and, all of a sudden, it’s very quiet — except for the hushed sound of teachers moving from table to table, answering questions and helping students work through the constant process of decoding brand-new words.

From the outside, it can seem quite complicated, but students are moving through it all with confidence and ease. In fact, one of the things you notice right away is how involved they are. Nobody appears to be sitting this one out: the answers are flowing, their fingers are moving, and new words are being unraveled.

After a while, there’s a well-deserved break in the action. Then, it’s back to learning.

Creativity and innovation in reading

Innovation 95

It may just sound like a lot of fun — and, to be honest, sitting in class, it does look entertaining — but everything happening this morning at Coker-Wimberly Elementary School is serious. These phonics lessons are part of an innovative literacy initiative that began here last year and has been introduced this school year at GW Bulluck Elementary and GW Carver Elementary, two more Edgecombe County Public Schools. It not only dictates how classes are conducted, but even how schools are run.

Formally, it’s known as the 95 Literacy Intervention System, but everyone around the school just calls it “95” — a numeral referring to the 95 Percent Group, an Illinois-based company that offers this curriculum grounded in the latest scientific research on how students learn to read best.

What unfolded in Boyd’s classroom this morning was phonics instruction, the core of this broader reading program, and it’s taking place today throughout the K-5 school. But that’s just part of the initiative. There are regular reading assessments that help provide important data so teachers can monitor the progress of each student overall — and to identify specific, essential skills where each could use more help.

During that “intervention” process, teachers can bring students together, even across grade levels, to work on those specific skills. It’s one of the real strengths of 95, but it also means the entire school schedule must be designed to provide those opportunities for students to become better readers.

There are a lot of reading programs out there, but this one is particularly strong in teaching what Principal Cassandra Harley calls “The Why.” Not just how to pronounce words, but why they’re pronounced that way — an advanced piece of the puzzle that clearly resonates with Harley, a science teacher, licensed reading specialist, and former Teacher of the Year.

Success together

This reading initiative is a years-long process that’s just getting started; the basic skills are being introduced in earlier grades, and some older students even need to recalibrate how they approach reading to take advantage of the new approach. But, so far, everyone is noticing a difference.

Latisha Hendricks sees the big picture. As literacy coach for Coker-Wimberly, she humbly describes her role as someone helping make sure that teachers are knowledgeable, confident, and ready to teach. That’s true, of course, but she also leads the entire effort in a sweeping job that includes managing all elements of the 95 program, training teachers as they enter the school, solving problems, gathering and analyzing data, finding additional resources and strategies, and teaching students.

She says there has been noticeable improvement for many students, even in these early stages, and the students are embracing learning. “The kids grab onto it,” she says. “They want to participate. It’s not a struggle to get them to participate.”

And it’s even making an impression at home. This isn’t how Shawnquilla Gray learned to read, so she’s picking up some of the new techniques from Skylah, her fourth-grade daughter. When they’re working together on homework, Gray has noticed that Skylah likes to read more. She asks more questions. And she sounds-out new words better than ever before. “I don’t have to stay on her as much as I have before,” Gray says. “She’s learning something more at school.”

Introducing anything so innovative and far-reaching takes a lot of people working together. Just in the classroom at Coker-Wimberly this morning, there were the classroom teacher, literacy coach, and Principal Harley, who occasionally drops into classes to see how things are going and spend a few minutes working with students. And many involved in the effort credit Superintendent Dr. Andy Bryan and his central office staff for being true advocates and going well beyond what school district leaders would normally do.

But that sense of cooperation doesn’t end with the schools. This entire initiative is possible thanks to Anonymous Trust, ChildTrust Foundation, and Barnhill Family Foundation, all area philanthropies that provided essential funding to hire a literacy coach and purchase the curriculum for each of the three schools. Bob Barnhill, president of the Barnhill Family Foundation, believes that giving students effective tools to read is particularly important because reading unlocks the imagination, inspires hope, and builds a foundation for success throughout life. He hopes what’s happening at Coker-Wimberly, GW Bulluck, and GW Carver will eventually have every student reading on grade level.

“Confident readers become confident people,” Barnhill says. “They find their voice and grow into empowered individuals who contribute meaningfully to their families, the workforce, and their community. Hopefully, that confidence will shine through Edgecombe County, and it will set the stage for lifelong learning, opportunity and generational impact.”

“This initiative shines a spotlight on the incredible dedication of teachers and leadership in ECPS. We have so much respect for the highly effective teachers who make a difference in their classrooms every day.”

— Bob Barnhill

Back in class

How it all happens doesn’t matter much to Marquette Burgess, one of the students learning new words back in Boyd’s class. He’s just interested in learning. Marquette is a real character — already headed toward the pastorate, he says — and no matter what question you ask, he eventually turns it back to how important it is to learn in school.

Explaining how he uses 95 to break down a new word, Marquette gives an example for “hippopotamus,” explaining the process while he draws imaginary lines on the table in front of him to separate syllables and using hand signals to show how each syllable sounds. So, all of this really makes reading easier? “95 helps me all the time,” he says. “It’s like that one power that I have that nobody can take from me.”

The literacy coach wasn’t in the room at the time, but she surely would have been pleased. Nothing will happen overnight, but there’s clearly been progress already, and she expects there will be much more to come.

“It’s already taking root,” Hendricks says. “We have begun planting seeds in fertile ground, our students. And through instructional literacy coaches, teachers and everyone coming together to make sure we’re confident with core instruction, we’re now watering and nurturing our kids. We are going to create blooming, proficient readers. We want to get this right for our kids.”

Editor’s note: The Anonymous Trust and ChildTrust Foundation support the work of EdNC.