Most teachers associate Project-Based Learning (PBL) with STEM. However, PBL’s benefits extend far beyond the hard sciences and can successfully be incorporated in the humanities. Social studies, language arts, and visual arts teachers can leverage PBL to immerse students in hands-on learning that encourages them to research, think critically, and develop a thirst for knowledge about the world around them.

PBLWorks (formerly the Buck Institute for Education), a nonprofit that trains educators in PBL methods, defines the practice as “a teaching method in which students learn by actively engaging in real-world and personally meaningful projects.” In other words, PBL empowers students to take ownership of their learning through project development. While traditional instruction can be passive, PBL challenges students to work on a product over a week or semester, inspiring them to problem solve and explore questions relevant to their daily lives.

‘Quilting Carolina’

As a veteran teacher with more than 30 years of experience, I feel I have a unique perspective and responsibility to help educators develop their teaching methods and leadership skills. For this reason, I have begun sharing the benefits of PBL and strategies for implementing it with fellow educators. In my social studies classes at Polk County Middle School, I utilize PBL to connect the arts and social sciences to STEM.

One of my more successful PBLs is an eighth grade social studies unit called “Quilting Carolina.” This multi-disciplinary unit combines art, math, and design with eighth grade history standards. Throughout the process, students learn about the history of quilting and quilt design and use their math skills to design a quilt square. Their square is then displayed alongside that of their classmates to create a complete quilt design.

Building buy-in through curiosity

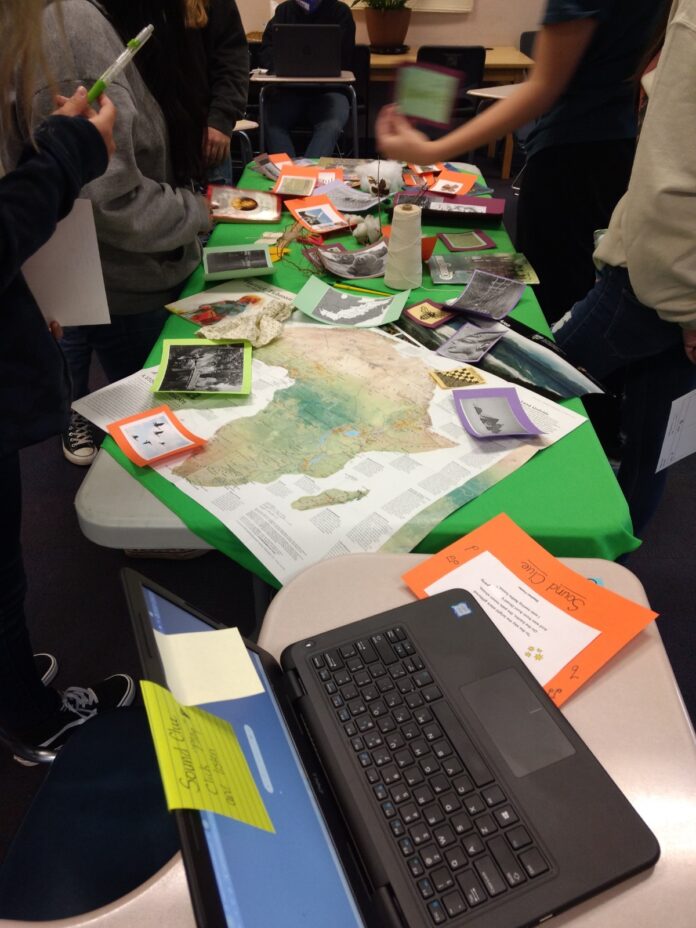

To gain buy-in from students, I start my PBL units with a dash of mystery. Using a strategy I learned from Dr. Megan Keiser at UNC-Asheville, I curate a “mystery table.” This method grabs students’ attention and sets the stage for them to be inquisitive and begin taking control of their learning experience. Although the method is for middle grades social studies it can be used for all grades and subjects.

On the mystery table, I place materials used in quilting, such as pieces of fabric, spools of thread, sewing needles, and historical artifacts, such as maps and sound clips from 19th-century American songs like “Aunt Dinah’s Quilting Party.” The unit’s name — “Quilting Carolina” — is kept secret until students can guess the topic or it is revealed.

Acting like detectives, the students observe and interact with the mystery table and write down what stands out, and what questions they have about the objects. Students then share their observations and questions in a debriefing session where they narrow down a possible topic for the unit. Engaging students in this investigative process fosters greater student agency.

Driving questions

Once the topic is unveiled, the students are ready to determine their essential question or what problem the unit will answer. In one of my classes, students developed the driving question: “How does quilting help us see history and change over time?” Throughout the unit, we revisit and even refine the driving question.

Having students come up with their own driving questions empowers them as they proceed through guided research to become experts on their chosen aspect of the topic. The goal is to move beyond passive learning and encourage students to question and problem-solve.

At the end of the unit, students honed their research skills, engaged with historical content relevant to their local community, and exercised their creativity by designing a painted quilt square. Traditionally, this unit on North Carolina folk history could have culminated with a written essay or a poster presentation. Those products are certainly effective ways of assessing how students retain and understand course content, but utilizing PBL challenges students to demonstrate leadership and tap into their project development skills.

Strategies for PBL success

Creating effective PBL units that inspire student engagement and further student inquiry is challenging, but not impossible. While there are core principles and standards for designing and implementing effective PBL units, there’s no one-size-fits-all method. Any educator regardless of grade level or content area can master PBL. Learning these strategies can further enrich teachers’ abilities to meet the needs of diverse student abilities and populations.

Want to learn how you can use these PBL strategies in your classroom? Join me from 5-6 p.m., ET on Thursday, March 20 for the second installment of Not Your Average PD, a free online professional development series for educators presented by the Kenan Fellows Program for Teacher Leadership.

Behind the Story

The author used Gemini to suggest how to clarify a paragraph, which was then rewritten based on those suggestions.