On June 11, 2025, advocates in health care and community-based organizations highlighted statewide innovations at North Carolina’s first Food is Medicine Symposium, hosted by the Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina Foundation.

The event focused on the collaborations between nine community-based organizations that the Blue Cross NC Foundation has supported and their accompanying regional health care partners. These collaborations have connected eligible North Carolinians with nutritious food tailored to their health needs.

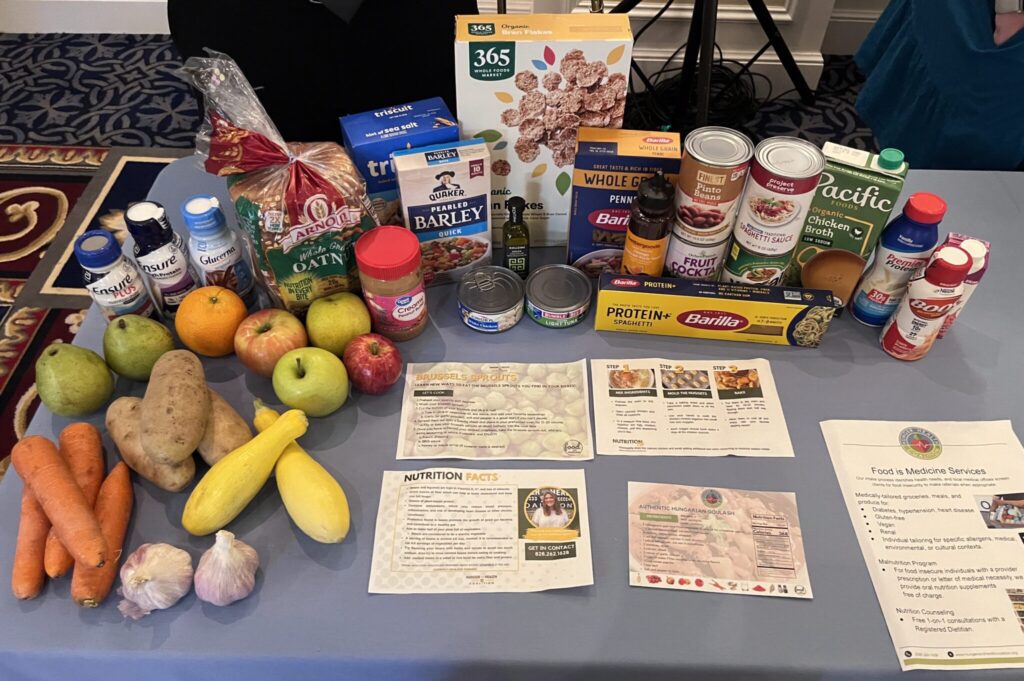

Food is Medicine is a health care intervention that recognizes nutritious food as a way to prevent and treat chronic diet-related health conditions and food insecurity. Health care providers assess patients who present diet-related illnesses or food insecurity and then prescribe a food-based intervention paid for by a health care provider.

This prescription is where community-based organizations come in, stepping in to facilitate that connection to local food and nutrition education.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

A report from the Aspen Institute revealed that these interventions – which can be medically tailored meals, medically tailored groceries, or produce prescriptions – are proven to reduce food insecurity, improve dietary intake, and improve mental health. While Food is Medicine efforts exist nationwide, the symposium highlighted how collaborations in North Carolina are in many ways leading the movement.

You can read the Blue Cross NC Foundation’s 2022 report on North Carolina’s Food is Medicine interventions, which are largely food prescription programs, here.

“The success of Food is Medicine in North Carolina would not have been possible without community-based organizations,” said Blue Cross NC Foundation President Dr. John Lumpkin in his morning keynote speech, referencing a Health Affairs article he co-authored with his colleagues Merry Davis and Valerie Stewart. “They’re the engine, the wheels, and the fuel driving so many Food is Medicine endeavors across our state.”

One of these organizations attending the event was the Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture Project (ASAP), an organization serving western North Carolina whose programming includes their Farm Fresh Produce Prescription program. In the program, eligible participants are given a produce prescription that they can redeem at several regional farmers markets.

Molly Nicholie, ASAP’s executive director, emphasized in a panel how the farmer’s market model goes beyond connecting people with locally-grown nutritious food. The relationships participants build with farmers and community members they meet at the market week after week, she said, speaks to the role the program has in addressing people’s need for community.

At the same time, ASAP’s Food is Medicine programming allows them to also focus on their mission to support small local farmers.

“We’re always centered on where can this help increase farm sales and build into those existing systems to be able to support farms not just as a one-off, but as a piece of their farm business plan?,” said Nicholie. “So it’s not just about making sure that they’re making a living, which is how we’re keeping farmers farming, but also about making sure that all segments of our community can feel pride in contributing to their success as much as they’re growing food.”

Across the state, Feast Down East’s Food Rx Program uses a voucher model to allow participants to pick out locally grown food. In partnership with Novant Health, participants receive $30 monthly vouchers to use at one of the program’s mobile farmers markets. While the market has a schedule visiting schools, community centers, and public housing areas, their partnership with Novant Health led to adding five different clinics in the Novant Health system to their routes.

Sarah Arthur, director of community health at Novant Health and one of Feast Down East’s board members, explained how the program has evolved to serve their community. For example, realizing that simply giving a participant a voucher and asking them to find a market in the community or sending patients with limited transportation options home with heavy food boxes was not realistically addressing their needs.

“So then we morphed into being physically present at our clinics where we knew we were giving out the most food boxes,” Arthur said, adding that this change included training clinic staff on screening patients and giving patients resources on the Food is Medicine program. “Then they can ideally shop that same day, if Feast Down East is there, or one of our community health workers can shop for them and bring the food to their home when they do a home visit with that patient.”

Susannah Spratt, Feast Down East’s mobile market manager, spoke to their program’s human-centered approach.

“We’ve learned a lot today about the freedom of voice and giving dignity and purchasing autonomy, and so we really pride ourselves on having that kind of model to be able to let folks decide for themselves and their families what makes the most sense for them. Because we’re also trying to be conscious of food waste and making sure that people are actually benefitting from the services that we’re providing,” she said.

Spratt also co-authored a Health Affairs article on cultural and place-based wisdom in Food is Medicine interventions that you can read here.

Both ASAP and Feast Down East are examples of how Food is Medicine operates from a generative approach to health care – one that Dr. Lumpkin explains should integrate and respect community-based organizations as true partners to health care providers, prioritize local food systems and their cultural relevancy, and recognize philanthropy as a partner in its future.

“What I’m talking about isn’t a fantasy,” Lumpkin said. “It’s not a wish. It is possible because it’s happening already. It just needs to be more of the norm, and that takes intentionality.”

Editor’s note: Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina Foundation supports the work of EdNC.