Last year, almost $700,000 of just over $3 million in state funding designated to help student parents at community colleges pay for child care went unspent.

For students enrolled at community colleges with children of their own, the rising cost of child care is a barrier to their enrollment and completion. North Carolina is one of a few states that has a solution to this problem with the N.C. Community College Child Care Grant program, which gives each of the 58 community colleges grant funding to distribute to their student parents to help them cover child care costs.

However, each year dozens of community colleges are unable to spend all of their child care grant funding.

EdNC spoke with representatives from the North Carolina Community College System and several community colleges to understand the barriers to getting this money to students and what we can learn from the colleges that are consistently spending all of their allotted child care grant funding. We found that while there are some barriers over which colleges have no control — for example, when the legislature passes the state budget — the grant gives colleges a lot of flexibility to determine local policies. The colleges that are successfully spending all of their funding each year have reevaluated their requirements for student parents and taken advantage of the flexibility to help as many students as possible.

Notice: JavaScript is required for this content.

The North Carolina Community College Child Care Grant is state aid directed to help student parents at North Carolina community colleges pay for child care. The North Carolina General Assembly (NCGA) has allocated this funding to North Carolina’s 58 community colleges since 1993, and it is administered through the North Carolina Community College System (NCCCS). Financial aid teams at each college are tasked with getting their student parents connected with the funding.

In the last three fiscal years (FY), funding for this grant has totaled $3,038,215 per year. In FY 2024-25, each of the 58 community colleges received a base allotment of $20,000 and an additional $10.16 per curriculum budget full-time equivalent student, or the number of curriculum full-time equivalent students for which a college is budgeted to serve.

Eligibility requirements

The grant program makes room for a variety of child care configurations, recognizing child care as a person, business, or organization that provides child care service to its clients. This means that student parents can use grant money to help pay for services from licensed or unlicensed providers, grandparents, nannies, afterschool programs, and summer programs. Parents themselves may not be paid for child care.

The NCCCS directs colleges to “jointly determine the need of student parents for child care in coordination with local social services agencies that provide child care funding for qualified students.”

In addition, the NCCCS says, “Funds must be disbursed directly to the provider or the student parent only upon receipt of an invoice from a child care provider accompanied by a student’s class attendance report.” The NCCCS stipulates that funds must be dispersed only after child care services are provided, and that they must pass a “reasonable test for cost.” For example, a student parent whose grandparent is providing child care services can’t submit an invoice that exceeds the average cost of child care in their area.

The N.C. Child Care Grant Program is just one way North Carolina’s community colleges support student parents. Community colleges have drop-in child care and licensed child care facilities on their campuses, host support groups for student parents, and support student parents with additional funding through scholarships.

A look at the data

General Statute 115-40.5, section 6.4, requires that the NCCCS produce an annual report to the NCGA with self-reported information from each community college. Because specific reporting requirements were amended starting with FY 2021-22, comparable information about funding allocation before the COVID-19 pandemic is not available.

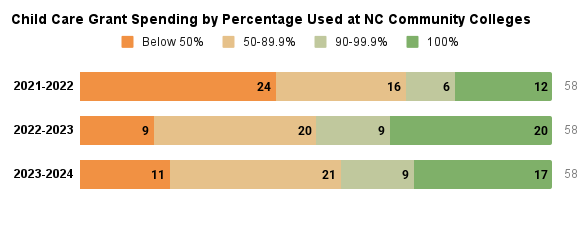

Looking at the data for the last three fiscal years, only about a third of community colleges have spent 100% of their grant funds each year. A little less than half of the colleges on average have allocated at least 90% of their child care grant funds. In FY 2023-24, 11 community colleges spent less than 50% of their funding, 21 spent between 50-90%, nine spent between 90-100%, and 17 spent 100%.

There has been an overall increase in funds expended since 2021-22 when colleges and students were dealing with the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. While there was a slight drop between 2022-23 and 2023-24, overall average growth in both funds expended and number of students served has plateaued in the last year.

Digging deeper into the data, the community colleges with the highest and lowest percentages of funds expended don’t appear to be systematically different from one another. The community colleges expending both the most and least grant funding include those serving rural, suburban, and urban counties as well as the most and least economically distressed counties. Child care deserts also exist indiscriminately among the counties these community colleges serve, with few exceptions.

However, trends internal to each characteristic can provide some insight into community colleges’ grant fund use.

Community colleges serving rural areas saw the greatest increase in funds spent (see figure below). Between FY 2021-22 and 2022-23, the average percent of funds spent for rural-serving community colleges jumped from 54.9% to 83.7% — an increase of 28.8 percentage points. While these numbers dropped in FY 2023-24, rural-serving community colleges allocated close to or more child care grant funding in the last two years than their suburban and urban counterparts.

Looking at community colleges’ child care grant spending by county economic distress rankings reveals that, on average, community colleges serving at least one Tier 1 county (most economically distressed) tend to spend a higher percentage of their funding (see figure below). Conversely, in two of the last three years, community colleges serving at least one Tier 3 county (least economically distressed) spent a lower percentage of their child care grant funding.

Over the last three years, six community colleges consistently allocated at least 90% of their child care grant funding to student parents.

Three community colleges consistently allocated 100% of their child care grant funding:

Two community colleges consistently allocated over 97% of their child care grant funding:

One community college consistently allocated over 90% of their child care grant funding:

What are the challenges in getting child care grant funding to students?

EdNC spoke with the system office as well as some of the colleges spending the most and least percentages of their child care grant funds to learn more about the opportunities and challenges in the grant’s implementation. What we found is that while there isn’t a one-size-fits-all formula for success, the key to getting money to student parents is taking advantage of the grant program’s flexible requirements. However, there are a few key challenges impacting colleges’ ability to take advantage of the flexibility and spend all their child care grant funding.

One challenge is the timing around when colleges receive the funding, which is dictated by the legislature. When the legislature doesn’t pass NC’s annual budget until after classes begin in August, community colleges don’t know what their operating budgets will look like. And, in turn, student parents don’t know if or when they will have crucial financial support from the grant.

“In the fall semester, students will come in, they want to register for classes, and we don’t know … if we’re going to have funding or how much we’re going to have,” said Brenda Long, Carteret Community College’s Director of Financial Aid. “So, you know, that prohibits, at times, the student from registering,”

“Every day that that state budget doesn’t come in, just at our school alone, dozens of students are affected,” added her colleague Maggie Brown, Carteret’s Vice President of Instruction and Student Support.

A second challenge is the lack of clarity around what they can and cannot do with the child care grant funding. Colleges have had a difficult time interpreting language in the State Board of Community Colleges’ State Aid Allocations and Budget Policies document.

The state’s aim is to allow colleges’ flexibility, according to Brenda Burgess, the State Director of Student Aid Programs at NCCCS. When first introduced, the Child Care Grant Program had stricter stipulations than the current version. For example, it was only in the late 2000s that the rules relaxed to include child care configurations beyond traditional licensed programs.

Now, virtually any form of child care is eligible under the program so long as it’s not one of the child’s parents themselves. However, two policies have caused confusion for colleges and have led to some taking a more cautious interpretation of the eligibility requirements, which makes it harder for student parents to access the grant money: whether the student parent has to formally document receipt of other child care funding sources from their local Department of Social Services (DSS), and whether the college is allowed to reimburse the student parent for child care services for which they have previously paid.

DSS documentation

Some community colleges have practices in place that ask student parents to document whether or not they are receiving child care-related funding from their local Department of Social Services. The NCCCS directs colleges to “jointly determine the need of student parents for child care in coordination with local social services agencies that provide child care funding for qualified students.” Many community colleges take this to mean they have to require that students obtain documentation of being waitlisted, denied, or actively receiving funds from their DSS, and therefore add these at-times cumbersome requirements to their administration of the grant.

Caldwell Community College and Technical Institute (CCC&TI)’s Financial Aid Director Ann Wright said the system office had to explicitly clarify what this language actually meant. Wright said that several years ago at a financial aid conference, Burgess asked community college representatives what challenges they faced in spending all the grant money.

“We all went, it’s DSS, can’t get that form filled out,” Wright said. “And that’s when she said ‘That is a best practice. It is not required.’”

CCC&TI, one of the colleges spending 100% of their funding over the last three years, has since eased their restrictions on requiring their student parents applying for the grant to provide a DSS letter.

Jami Dandridge, the Director of Financial Aid and Veteran Services at Sandhills Community College, said that in the last couple years she realized many of Sandhills’s requirements previously in place were actually not required by the state, including around DSS documentation.

“Every single person had to go to DSS and apply, go through that process and get some type of letter,” Dandridge explained. “That was just such a deterrent. I would be deterred.”

Now, the application asks the student parent whether or not they receive DSS funding. Those who answer ‘yes’ have to provide a letter from DSS, but no one else does.

When EdNC asked Burgess about this, she clarified that colleges should make sure that they aren’t giving student parents more grant money than they need if they’re already receiving DSS funding, but that they should not make it a barrier for students if the process for documentation is difficult and time consuming.

Reimbursing student parents

A less-clarified point of confusion that is hindering grant expenditure is whether or not colleges are allowed to reimburse student parents for child care expenses. The language says, “Funds must be disbursed directly to the provider or the student parent only upon receipt of an invoice from a child care provider accompanied by a student’s class attendance report,” followed by, “Neither the student parent, nor the other parent of the child may be reimbursed for services.”

While the first sentence says colleges are allowed to reimburse student parents for child care expenses they have paid for out-of-pocket, some colleges are interpreting the second sentence to mean that students can’t be reimbursed at all and the money has to be paid directly to child care providers.

“At Sandhills, part of the interpretation was that you don’t pay the parent directly,” Dandridge said. “I started going, ‘wait, wait, wait, wait, guys, I feel like this says we can pay them if we have proof that they attended.’”

When EdNC asked Burgess to clarify this, she said colleges are able to reimburse student parents for child care services for which they’ve paid so long as it’s part of their adopted procedure.

Both Carteret and Sandhills community colleges told EdNC they’re now using the funding this way because they interpret it as allowable and a crucial “no-brainer” way to help the money get into student parents’ hands. For example, a newly transferred student parent might not have known about the grant until halfway through a semester, or the General Assembly might not pass a budget releasing the funds to colleges until after the fall semester begins. In both of these scenarios, a student parent would’ve had to cover some or all of their child care costs out of pocket for some portion of the semester. Reimbursing the student parent for the child care they’ve paid for is a huge financial help to the student, although it requires that student parents are able to pay the bill upfront.

Brown at Carteret Community College explained that encouraging students who already qualified for the grant and have invoices showing out-of-pocket child care costs the grant didn’t cover and class attendance records to come in and receive any remaining child care grant funding at the end of the year is a key factor in allocating all their money.

Solutions for moving forward

The NCCCS is working on creating clearer language about the requirements, Burgess said, so that colleges are confident about what is actually expected of them. Burgess acknowledged that the wording colleges receive is difficult to interpret and explained that the system office is working to clarify it to be ready by, hopefully, next year’s grant cycle.

“Going forward, we want to be able to change that language and/or make it…a little less stringent than it appears to be,” she said.

While community colleges wait on this state-level change, several have already begun reevaluating their processes to identify and remove grant requirements that are not mandated by the state. While no community college is the same and each serves a unique population, dictating the procedures and rules they need to have in place, colleges have realized they may be imposing barriers that are not actually required.

When it comes to who is actually eligible for the grant, “It’s pretty much at the discretion of the colleges,” Burgess said. In other words, it’s up to colleges to decide on procedures for distributing the grant to their student parents.

An initial scan of community colleges’ public-facing application materials reveals that they indeed have adopted varying requirements. Some schools have adopted a more cautious interpretation of the eligibility requirements, which has made it harder for student parents to get access to grant money.

Generally, all student parents must be a legal North Carolina resident, maintain academic eligibility or meet minimum GPA requirements, and have completed that academic year’s FAFSA application. Some colleges also appear to prioritize single parents, parents that are returning students, and full-time students.

At some colleges, only students enrolled in in-person degree-seeking programs are eligible for child care grant funding. Others have the grant open to both curriculum and continuing education students.

Wright said that despite the fact that CCC&TI’s grant funding supports fewer continuing education students than curriculum students each year, she still sees it being open to both as a “model for the state” because it makes it easier for a student parent seeking child care financial assistance.

“CCC&TI is about removing barriers to resources,” Wright said in an email.

Another barrier CCC&TI removed is requiring student parents to be taking in-person classes.

“We used to not provide child care assistance for online students,” said Dr. Mark Poarch, president of CCC&TI. “And I think the thought at that time was, ‘Well, the parent’s at home with a kid, they really don’t need child care assistance,’ when, in fact, they probably needed it just as much as a student coming to class in person just to be able to focus on their academics.”

Dandridge similarly explained that reevaluating Sandhills’ eligibility requirements, particularly their requirements around DSS reporting, made a big difference in the amount they have been able to spend. In FY 2021-22, Sandhills spent just over $2,100 of their child care grant — roughly 4% of their total allotment. This most recent fiscal year, that number jumped to over $12,500, or about 25% of their total allotment.

To get more money into the hands of her student parents, the question Danbridge asked and answered was: “Are we doing this to ourselves, or is this, in fact, something that they [the state] want us to do? And what we kind of found was that a lot of things we were doing to ourselves, and in turn, we were doing that to the students and just making it a little bit harder when maybe it didn’t need to be.”

Finally, colleges that have been successfully spending all of their grant money have adopted processes that enable them to easily find eligible students and get the grant funding to them.

If they have any leftover grant funding, Carteret Community College reaches out to eligible students and lets them know they can bring in receipts for child care services to be reimbursed if they have not been reimbursed already.

Piedmont Community College keeps a waitlist of eligible students and contacts them as funding becomes available.

“How we get to that almost 100% every year is keeping that waitlist and having someone ready to jump in if anything happens,” explained Shelly Stone-Moye, Director of Student Aid at Piedmont.

Stone-Moye, along with every other community college representative EdNC spoke with, also emphasized the importance of making sure student parents knew the grant was available to them by intentionally marketing the program (think emails, events, flyers), encouraging faculty to point their student parents toward the grant, and by creating a reputation among the student body that their financial aid services are there to help their student parents succeed. Each couldn’t emphasize enough the importance of the grant to their student parents’ persistence and completion.

“Financially, it’s that security that they can continue their education and not get stopped by all of a sudden having to cover a child care bill,” Wright said.