(WGN) – Herpes can cause cold sores and fever blisters, and it may also hold the key to understanding cancer.

One scientist has spent 30 years studying a virus so ubiquitous that it’s estimated to affect 80% of the global population. And now, he and his team say their findings may apply to another disease impacting millions.

Dr. Deepak Shukla, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Illinois Chicago, leads the research. The virus is herpes simplex 1.

“(Herpes) is a quiet virus. It just quietly likes to live in our neurons,” Shukla said.

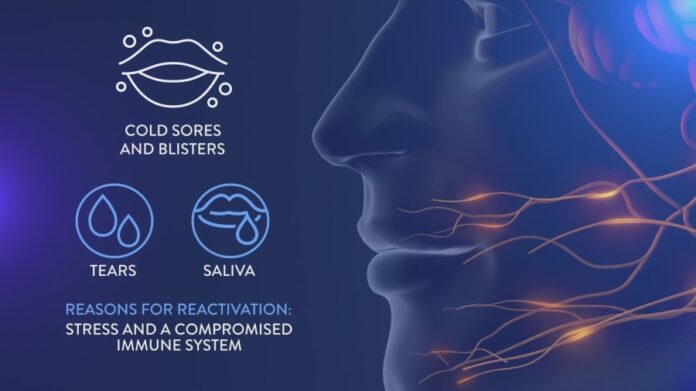

Herpes hides in the trigeminal nerves that stretch to the eyes, nose and mouth, where it commonly produces a cold sore or fever blister. It’s spread through tears and saliva. Stress and a compromised immune system can reactivate the virus.

“So there is a constant battle going on between the virus trying to replicate in our neurons and (the) host system trying to suppress it,” Shukla said.

To determine the impact herpes has when it spreads from the eyes or nose, the team injected the virus directly into the nasal cavity of mice.

“The virus caused havoc in their brain, killed or inflamed a bunch of their neurons and that could be all different kinds of neurons,” Shukla said.

The herpes virus’ impact on the brain changed the animals’ behavior – the mice were anxious and experienced motor impairment and cognitive issues.

“What we showed with (the mice) is an extreme possibility, but over time, since the virus is hiding in our neurons and it’s periodically reactivating, something similar could happen in humans, too,” Shukla said.

A specific enzyme called heparinase played a critical role in inducing damage in the brain. It’s the same enzyme known to increase in different forms of cancer.

“Not just simple cancer but these are metastatic forms of cancer … majority of them have high heparinase,” Shukla said.

Heperinase protects cells from dying – a good thing in healthy cells. But when a cell is infected, it too wants to live. That’s where heperinase and herpes appear to work together to promote spread. The same might be true in cancer cells. When heparinase wasn’t present, Shukla said, there was an interesting finding.

“Animals that did not make heparinase at all,” he said. “They were fine, they did not have any issues — same amount of virus same rate.”

Shukla says the ultimate goal is to teach heperinase the difference between good and bad cells.

The next step is to develop a non-toxic heparinase inhibitor they can test in animals and ultimately humans.