“I’ve been an advocate for a long time. I love children. I love families. But at some point, your hands are tied. What can you do?”

That’s what Cassandra Brooks, owner and operator of Little Believer’s Academy, says she’s been asking herself lately. She kept her small business running with the help of stabilization grants during and after the pandemic. Those grants expired at the end of March.

Brooks told EdNC that unless something dramatic happens this legislative session, she’ll need to seriously consider closing her five-star centers.

Based on data provided by the N.C. Child Care Resource and Referral (CCR&R) Council in partnership with the state Division of Child Development and Early Education (DCDEE), EdNC has found that North Carolina lost less than 6% of licensed child care programs during the five years when stabilization grants were used to supplement teacher wages. Centers such as Brooks’s fared better than family child care homes, which make up 88% of net losses statewide.

Of the state’s 100 counties, 65 have had a net loss of licensed child care programs since February 2020, while 14 have remained stable and 21 have experienced a net gain.

Data that include licensed after-school care can be found using DCDEE’s NC Early Care and Learning Data Dashboard.

Updates from DCDEE

DCDEE has been emailing quarterly updates on stabilization grants to relevant parties for the last five years. The most recent update included a brief timeline of the grants:

Money for Stabilization Grants came from the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA), a federal response to the COVID-19 pandemic. This one-time-only funding ended June 30, 2024. In September 2024, North Carolina lawmakers amended the budget to give DCDEE $67.5 million to continue only the compensation support component at a reduced rate from July 2024 through December 2024. Then the N.C. General Assembly passed Session Law 2024-57 in December 2024, $33,750,000 to continue only the reduced level of funding for the compensation support component of the Child Care Stabilization Grant for January-March 2025 (Q13). Since the January-March 2025 payment, no new federal or state funds have been given to DCDEE to stabilize North Carolina early childhood education programs.

EdNC has been tracking licensed child care closures since October 2023. With the end of stabilization grants, we asked DCDEE how the grants affected the availability of early care and learning in North Carolina over the last five years.

In an emailed response, James Werner, a DHHS press assistant, said, “Investments in teachers pay off. North Carolina used one-time federal child care stabilization funding to increase early childhood teacher salaries and pay bonuses. As a result, our early childhood education network fared better than those in most other states.”

More of EdNC’s closure coverage

States could choose whether to use the bulk of their funds for ongoing operational costs such as wages, benefits, and rent, or for one-time costs such as facility upgrades or classroom supplies.

Werner pointed to the findings of a report done in collaboration with the Frank Porter Graham Child Institute indicating that stabilization grants played a positive role in preserving North Carolina’s early care and learning infrastructure.

“With much of the funding being used to increase teacher salaries, bonuses and benefits, fewer child care programs closed than expected based on pre-pandemic trends,” Werner said. “Due to stabilization grants, the total number of programs decreased less than expected had a pandemic not occurred.”

Subgroup trends

The western counties that make up the area covered by the Dogwood Health Trust (Avery, Buncombe, Burke, Cherokee, Clay, Graham, Haywood, Henderson, Jackson, Macon, Madison, McDowell, Mitchell, Polk, Rutherford, Swain, Transylvania, and Yancey) have experienced a net loss of 4% of licensed child care programs over the last five years.

In the eight majority-Black counties (Bertie, Edgecombe, Halifax, Hertford, Northampton, Vance, Warren, and Washington), the number of licensed child care programs has fluctuated since 2020, but returned to pre-pandemic levels as of March 2025.

Robeson and Swain both have large indigenous populations, and together have had a 5% net gain of licensed child care sites, mostly due to Robeson County. EdNC is still interested in learning why that is.

How closures are harmful

When an early care and learning program closes its doors, whether it’s a multi-classroom center or an educator’s home, the negative effects are immediate for students and their families.

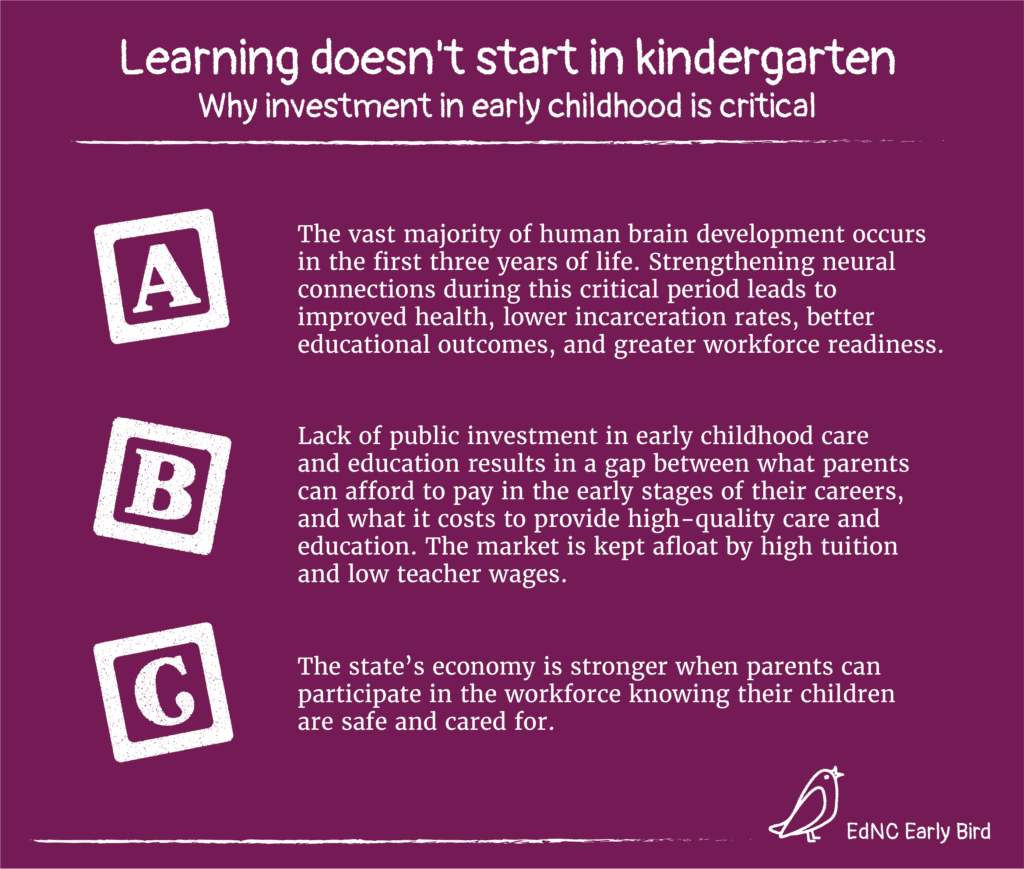

Any sudden change in caregiving can inhibit healthy brain development during the critical years between birth and kindergarten. Stable, loving adults have an outsized positive impact on the developing minds of our state’s littlest learners — and losing such an adult due to a program closure has an inverse effect.

When a site closes, parents are often forced to miss work as they scramble to find appropriate care for their children. And when options are limited, families have less freedom to choose the type of high-quality care that’s best for their children.

For the educators who have committed themselves to caring for and teaching infants, toddlers, and preschoolers, program closures often mean not only the loss of their livelihood, but pivoting to a new career, one that may offer family-sustaining wages, but for work they find less meaningful.

Brooks used the stabilization grants to pay higher wages, with a focus on recruiting teachers with higher levels of education attainment to work at her five-star center. Without the grants, she’s worried about making payroll.

“I love my teachers. Some of them have been working with me for many years, and I appreciate them,” Brooks said. “But no matter how much you care about a person and love them, if you can’t get the money to pay the payroll, it won’t matter at all, and it’s a disservice to them.”

Brooks said she’s been talking to other child care providers who find themselves in the same situation, but even those who are trying to sell their centers are facing a new challenge.

“They have a hard time selling businesses because private equity groups, meaning the larger corporations, the KinderCares and stuff, they’re not even buying right now because they know it’s a fiasco,” Brooks said.

She said she was hopeful that people would come together from a wide range of professional fields and political backgrounds to think outside the box and find a solution to the child care crisis that’s been growing for decades, but she’s having a harder and harder time remaining optimistic.

“This is not a Democrat issue or a Republican issue,” Brooks said. “This is everybody’s issue.”