The Saturday in September after Hurricane Helene hit Watauga County, David Jackson found himself walking the aisles of the local Harris Teeter, the only grocery store in town with power.

“We were all just kind of wandering around, not really with an agenda, just like, it was a place to be,” said Jackson, president and CEO of the Boone Area Chamber of Commerce.

He bumped into Halee Hartley, owner and operator of Kid Cove, a child care program with three sites in the area, who is also a member of the chamber’s board.

Hartley was buying food and water for the families she serves. She also was considering closing her program.

“When the storm hit, I could not charge my 125 families tuition knowing that some have lost access to their homes,” Hartley said. “Some are moving away temporarily to just be in a safer place. But here I am. Rent is still due. Bills still have to be paid. I still have 42 employees that have to be paid. So in my mind it was, ‘OK, I’m just gonna shut my doors.’”

That encounter in the grocery store set Jackson into motion. These kinds of disruptions in child care meant a harder road to recovery for all businesses, he said.

“That was one of the first moments for me that was like, ‘We’ve got work to do here,’” he said.

In the following week, the local chamber announced it would cover the majority of child care programs’ tuition for October. BlueCross BlueShield of North Carolina Foundation, a private philanthropy, chipped in for a $280,000 total investment so programs could keep paying their teachers while they lost revenue.

For Hartley, the funds kept her going through the fall.

“That was huge,” she said. “All three of my facilities did have damage, but we got in there quick because we knew that people had to have child care right away.”

Now the chamber and its local partners are pushing for both public and private investment in Watauga County and across the state to alleviate the burdens that a lack of child care is putting on providers, businesses, and families.

“We want Boone to come back stronger than ever, and that’s why we want to do everything that we can to help this community and others in Western North Carolina solve one of our biggest challenges, and that’s access and affordability in child care,” said Erica Palmer-Smith, executive director of NC Child, one of several state and local groups that convened Tuesday in Watauga County to hear from educators and experts, visit providers and businesses, and discuss solutions.

‘An established path’ between business and child care

Several years of community work led to the moment in the grocery store, Jackson said. The speed with which the chamber funds made it to local child care programs was due to pre-existing relationships and a common understanding that child care is a necessity for the local economy.

The chamber, along with the Watauga County Economic Development Commission and the Children’s Council of Watauga County, started an initiative before the pandemic to understand the need for accessible, affordable child care and to find solutions. They created a local early childhood fund to which businesses, private foundations and individuals, and public entities could contribute. In April 2024, the group released a study highlighting how child care challenges keep parents from working. The study found that the county needed 579 more child care slots, which would add 300 employees to Watauga’s labor pool.

“We have put that public-private partnership mechanism in place that was a benefit to us when things got disrupted in September,” Jackson said. “We had an established path between the business community and the early childhood community.”

Business owners across the state and country are identifying the lack of child care as a barrier to recruiting and retaining employees. Local chambers, as well as the state and national chambers, are releasing studies, convening stakeholders, and advocating for both private and public solutions.

“Child care is an economic development imperative; it is not merely a social issue that affects women and children,” said Samantha Cole, child care business liaison at the state Department of Commerce, at the advocacy day Tuesday.

The chamber welcomed local and state leaders in business, early learning, and government to showcase the county’s efforts to come up with cross-sector local solutions and to push for statewide ones.

Affordable, accessible child care could add up to 68,000 jobs in the state, increase its annual economic output by up to $13.3 billion, and boost its GDP by up to $7.5 billion, according to an October study by the department and NC Child, a nonprofit advocacy group.

Cole’s job is to help interested businesses of all sizes engage in child care solutions, from hosting on-site programs to subsidizing employees’ child care costs to spreading awareness and advocating for change.

Watauga hosts several local examples, Cole said. The group visited Blowing Rock Academy on Tuesday to see a unique model in motion: a child care facility built and operated by the Town of Blowing Rock for the children of its employees.

“Regardless of the scale of your business, your industry, what your budget is, how many workers you’re employing, the truth is, every organization can get meaningfully involved in this problem at any budget,” Cole said.

‘More significant public investment’

The state legislative session kicked off this month and will be creating a new two-year budget in the coming weeks. And although employers have a role to play in child care access, public investment is essential, Cole said.

“Those innovations are wonderful, and we also have to see more significant public investment come into the picture to make sure that child care resources are undergirded, so that all these ideas and innovations and creative notions we’re seeing be successful in local communities can continue to thrive, grow, scale across the state,” Cole said.

Sen. Ralph Hise, a Republican who represents Watauga and eight other western counties, attended the event. Hise, who chairs the Senate appropriations committee, said child care programs in rural communities are relying heavily on child care subsidy, a program to help low-income working families afford care, which is funded through a mix of federal and state dollars.

That subsidy does not cover the full cost of care, and in Watauga County it provides programs with a lower rate per child than in all surrounding counties, Palmer-Smith said. For an infant, a five-star facility receives $822 per infant per month.

Hise said that in many cases, programs receive even less per child because of a state rule that prohibits programs from getting more than their private rates.

“There is no ability for centers, particularly in rural areas, to raise private cost,” Hise said.

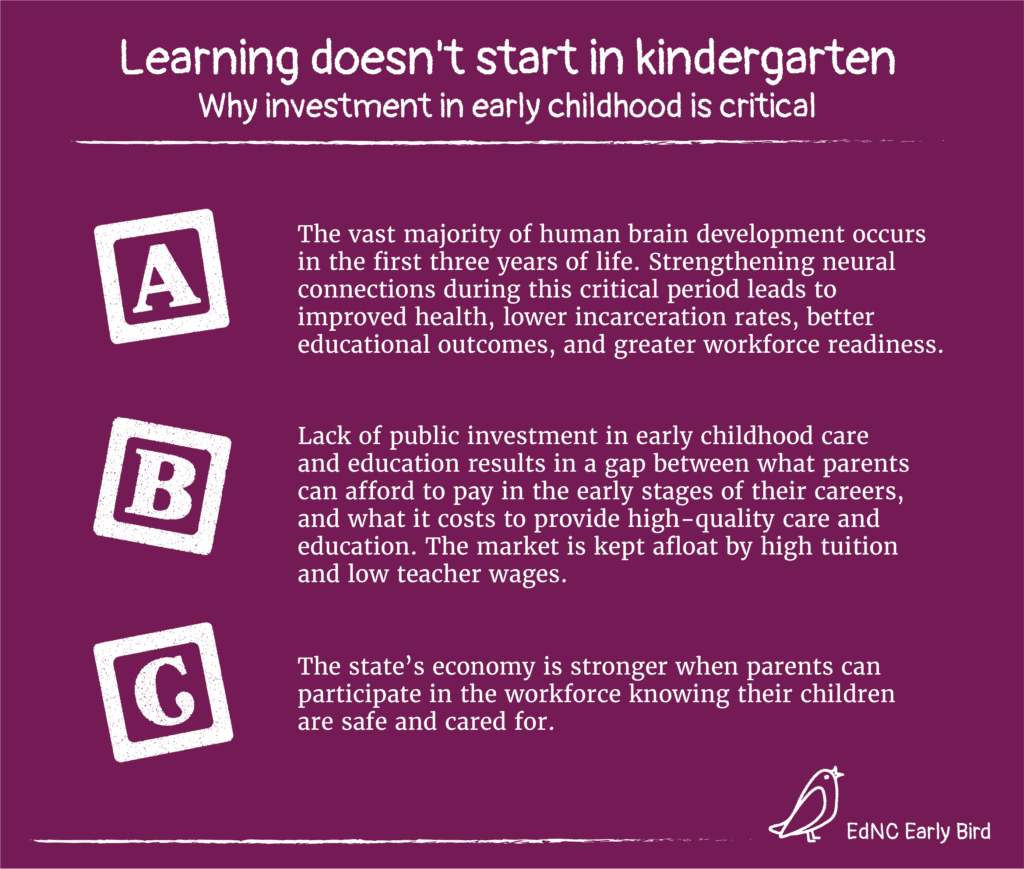

This calculation, of how to remain open without sufficient revenue, is based on the labor-intensity of the industry. Programs are unable to charge parents what it costs to run a high-quality program that recruits and retains staff with competitive wages. Sources of public funding, such as child care subsidy, are also limited.

This leads to shortages in care, especially for the youngest children, whose care is especially labor-intensive.

“Most centers have to offer enough after-school care to subsidize the birth-2,” Hise said. “But the challenge is that if you look at early childhood development, our investment needs to be more in birth-2 than it does with older students. But the bulk of our investment is in 4-year-olds, and the bucket of profitability for centers is after-school care. It really becomes this mismatch of the funding sources… It’s a hard puzzle to put together for any kind of center. It is not, ‘Look at the needs of the community, and how can I meet them?’”

This balance is one that Hartley is navigating day to day.

“We are just going payroll to payroll, paying the bills, because pre-storm we had a 1% profit margin, but now it’s like, we have put so much money into repairs, and we have put so much resources into helping our families that we don’t really have extra right now,” Hartley said.

The General Assembly in October approved $10 million in Helene relief for licensed child care programs in storm-impacted counties. That funding has yet to be distributed.

And in November, legislators approved $33.75 million to continue compensation grants to child care programs through March, a funding stream set up by the federal government during the pandemic.

Hartley said sustainability is needed beyond one-time allotments.

“We need some more long-term funding addressed,” she said. “North Carolina had a child care policy disaster before the natural disaster when Helene hit WNC. This has exasperated many of the long standing issues and the funding instability of the child care sector.”

‘Nothing but a huge success’

As child care arrangements fell through for employees of the Town of Blowing Rock during the pandemic, parents started bringing their children to work.

“We kind of started a de facto child care center without really meaning to from COVID,” said Shane Fox, Blowing Rock town manager.

The need for reliable, affordable care became apparent.

“We started having conversations with our council members about the fact that we were seeing younger and younger employees coming to the town, especially in public safety within our police department,” Fox said.

Three years ago, Fox pitched the idea of building a licensed facility to offer care for the children of employees at a discounted price. The Town Council approved the program, which opened in March 2024.

Blowing Rock Academy, a five-star licensed center, serves 10 children full-time, with another three infants to be enrolled in the next couple of months. It offers full-day care for employees at about half the market rate, or $400 per month, regardless of the child’s age. The program employs a director, at a $60,000 salary, and one teacher at a $40,000 salary. Part-time staff, Fox said, earn between $16 and $18 an hour, depending on education.

“It really does feel like one big family,” said Kristy Hayes, who works for the town in human resources. Her son Wesley, now 2 years old, was one of the first children enrolled in the program.

Fox said the program operates at an annual loss of about $125,000. The town pays about a million dollars per year for health insurance coverage for its 100 employees.

“It’s not something we take lightly, but it’s also something that we want to put in perspective,” Fox said. “We spend a lot of money on benefits as a government… I think that’s why we were successful in recruiting and being able to retain people.”

He said the cost of recruiting and onboarding a single police officer is almost as much as the cost of the child care facility each year.

The child care benefit has drawn employees to the town, with both a new police officer and a teacher coming from the school system to access child care.

“It has been nothing but a huge success, not only internally, but a huge success on the outside,” Fox said. “We’ve got a lot of folks within the state that have come and visited and toured the center, other municipalities and other counties looking to do something very similar. So we’re just excited that maybe this helps launch others into this kind of endeavor, because I think it is only beneficial.”