In the last 18 years, Wilkes County has lost 56 child care programs, 67% of its child care capacity. This year, thanks to a scrappy community effort, local leaders saved the county from losing another.

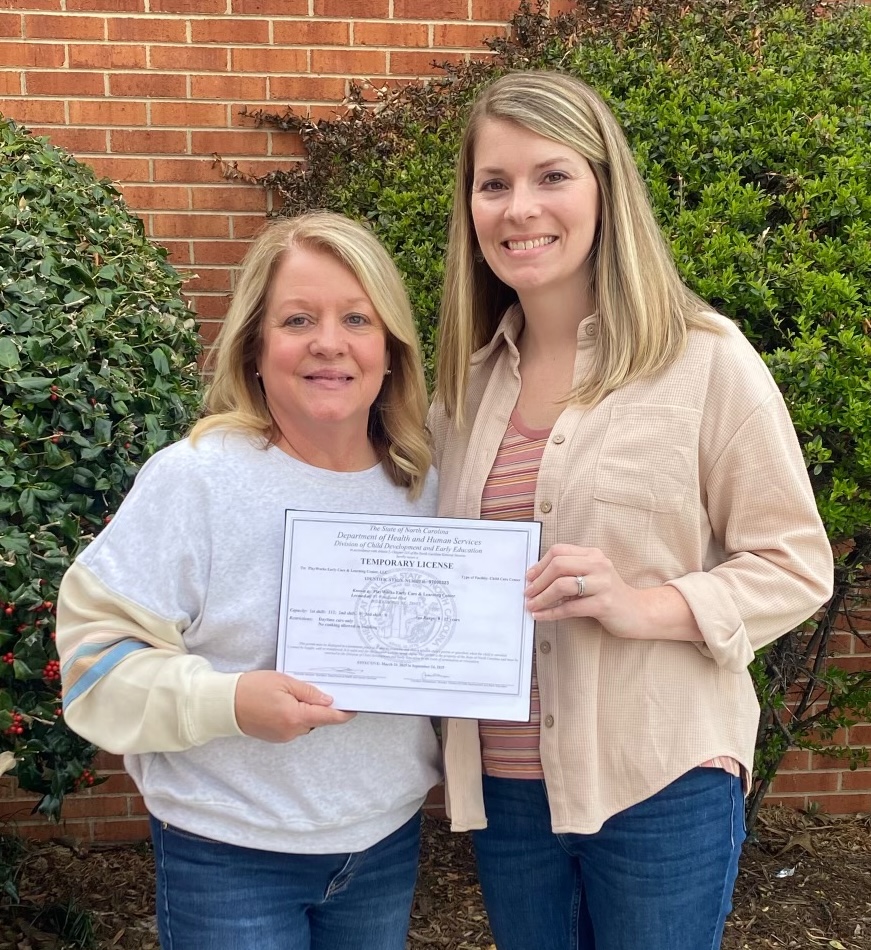

Sharon Phillips and her daughter Katy Hinson, owners of PlayWorks Early Care and Learning Center, cut the ribbon on their new location inside Wilkesboro United Methodist Church in April, expanding their business after months of wondering whether they’d survive at all.

“I consider what happened there a miracle,” said Todd Maberry, former managing director of the Ormond Center, a project at Duke Divinity School focused on helping churches assess their communities’ needs and find new ways to meet them. The center, which is closing this summer, helped the Wilkesboro church decide how to use an empty wing to help address a local lack of child care and bring in new revenue.

The specifics of the initiative, called “Big Building, Little Feet” — both the people behind it and the speed at which they raised more than $600,000 as the five-star program faced eviction — are specific to this community. But the model itself, Maberry said, has lessons for the entire state.

“There’s not one of the 100 counties that doesn’t have a church that has an empty educational wing sitting there,” Maberry said. “This can be a blueprint.”

With pandemic-era child care funding gone and bipartisan state leaders prioritizing child care solutions, local leaders like those in Wilkes County are convening, collaborating, and raising money to make things work for their neighbors in the meantime.

“Communities need to think outside the box,” said Michelle Shepherd, executive director of Wilkes Community Partnership for Children, the local Smart Start partnership. “I think that’s the biggest takeaway. These children deserve quality child care, and what does that look like, and what do communities have to offer?”

A child care need, a church need

In 2023, Phillips and Hinson were touring every vacant building in town.

They were looking for a larger space to expand their 10-year-old business and help fill child care gaps. That year, a study funded by the Leonard G Herring Family Foundation found that the county needed 836 additional child care slots, almost double the capacity it had. The report’s findings, released by the Wilkes Economic Development Corporation (EDC), were starting conversations in the business community.

“The child care study revealed what a crisis we were in,” Hinson said.

Hinson and her mother were already struggling with a balance familiar to child care owners. They did not have enough revenue to pay teachers much more than minimum wage, couldn’t raise tuition without pricing out families, and were unwilling to cut costs by lowering quality. Stabilization grants funded through the federal American Rescue Plan Act were expected to dry up, leaving a large gap in the budgets of programs across the state.

“We just kind of felt like we had done all we could on our own two feet,” Phillips said.

Phillips and Hinson were coming up short in their search.

“We had knocked on doors, we had toured all the vacant buildings, we had been to town officials,” Phillips said.

Then they started conversations with a local entity with its own financial struggles: Wilkesboro United Methodist Church.

“Our church has dramatically shrunk … especially post-COVID,” said Gilbert Cox, who has attended the church since 2008 and was the chair of its finance committee at the time.

Cox recalled holidays when he first joined with people overflowing into the aisles and Sundays with regularly full pews. A couple of years after the pandemic, the church was lucky to have 50 members attending services.

“This is a very common story for a lot of congregations in the country, particularly in North Carolina, particularly in rural places, where mainland churches have just been decimated by a pandemic, by disagreements,” Maberry said. “And Wilkesboro is not immune to that.”

Plus, more than 90% of the church’s space was sitting unused more than 90% of the time, Cox said.

“Eventually, what was an asset was going to turn into a liability,” he said. “The maintenance of it, and it stored more and more. I think we found five pianos. There were two in a closet we didn’t even know about.”

The church entered a six-week “design sprint” with the Ormond Center called the Community Craft Collaborative to figure out a different path forward. The process aims to helps churches better understand their community through data and interviews, and then encourages them to come up with an idea to experiment with.

Through a conversation with the EDC, Cox learned about the child care study’s findings. The organization connected him to Phillips and Hinson, who had recently reached out in their search for a new home.

By the end of the sprint, the church presented its idea: house and expand PlayWorks. Phillips and Hinson toured the church’s facilities and heard from the church’s leadership that they were on board.

“How could we take what is becoming a liability, and better connect to the community?” Cox said.

‘A gut punch’

In April 2024, a contractor gave an estimate on the building renovations necessary to meet regulatory standards. It would cost about $1.6 million. Everyone involved agreed: “It was insurmountable,” Cox said.

The potential collaboration felt like it had died, and Phillips and Hinson were back to square one.

“Everybody ghosted,” Phillips said.

While they were already down, they were hit with what Phillips described as “a gut punch.” In June 2024, the program received an eviction notice from its landlord, a local theater company that wanted to repurpose the space. PlayWorks had to be out by September. Their hunt for a new building became a make-or-break endeavor.

“I can just remember thinking, what are we going to do? What are we going to do? We don’t have any choices,” Phillips said. “I immediately called Michelle at the partnership.”

Shepherd, who had been the executive director of Wilkes Community Partnership for Children for about a year, said she immediately understood the urgency. With a background in K-12 education, Shepherd had spent her time at the partnership learning about just how dire her county’s child care needs were and developing relationships with a whole new sector of educators.

“We just couldn’t let them fold,” she said.

Shepherd’s leadership was a game-changer.

“When she wouldn’t give up, I wouldn’t give up,” Phillips said.

Through a $15,000 grant from the Ormond Center, the church paid an architect for renderings, moving forward without knowing whether things would work. Through a stroke of luck, a local contractor was called in to do the building’s measurements who was interested in bidding on the project. This time, the estimate came in at about $600,000.

“Michelle says, ‘Don’t give up,’ so it breathed new life into the possibility,” Cox said. “Even though the church didn’t have $590,000, Michelle — she deserves all the credit — she said, ‘Let me see what I can do.’”

Time crunch

Everyone got busy. Hinson and Phillips asked their landlord for an extension on the move-out date. The church began a deeper process with the Ormond Center to map out the details of the project. Shepherd, with no fundraising experience, started making calls.

“We all stepped out in faith that it would happen,” Hinson said.

The child care study helped Shepherd tell potential donors the story of the community’s need, she said, and explain the importance of child care for workforce participation.

“This was not some ‘Betty Froo Froo’ project; this was a necessity for our community,” she said. “That really played on the heart of business people in the community.”

Hinson and Phillips got an extension from their landlord for their move-out date to November, and then to April 2025.

Once Shepherd received the first big ‘yes’ — a $250,000 donation from an anonymous community member — others started following.

“That was my big driver, that we can’t tell these kids, ‘You’ve got to go home,’ and parents that they can’t work that really want to work,” she said.

She reached out to people with a connection to PlayWorks, who understood the importance of the high-quality care and education it provided for children and families. She received donations from dozens of individuals, including a large contribution from private donor Janice Story and funds from church members and partnership employees.

She also reached out to foundations and community groups, securing grants from the Carson Foundation, the Leonard G Herring Family Foundation, the Cannon Foundation, the North Carolina Community Foundation, and United Way of North Carolina.

The effort did not receive any local or state public funding.

“All of a sudden, Michelle had almost a half a million dollars in a matter of almost weeks,” Cox said.

The Ormond process provided real estate and zoning expertise, as well as a video crew to help the community tell its story. It was rooted in “asset mapping,” Maberry said.

“We’ve got a church with empty space, we’ve got an incredible child care center that is flexible and can move, and we’ve got a local nonprofit that’s committed to the well-being of children in the county,” he said. “Those are great assets. They can begin to look at, ‘OK, well, there’s a child care crisis, and one of the better ones is about to go away. How do we solve that?”

Shepherd said her mother was a salesperson, and always told her that salesmanship requires a good product and a powerful “why.” She had both.

“We had people that gave $50 up to $250,000,” she said. “It truly was a community, dollar-by-dollar fundraiser.”

Making it to opening day

From November 2024 to March 2025, the team reached their goal. The local contractor agreed to start construction before all the funding was secured to help Phillips and Hinson reach their move-out deadline.

There were many obstacles. The team almost had to call off the project once again when they realized the extent of the plumbing needs to have appropriate sinks in each room. They coordinated between sanitation, the county inspector, fire safety, and the state child care licensing under the Division of Child Development and Early Education (DCDEE).

“There was not a single source that you could go to who could give you all the answers,” Cox said.

PlayWorks closed on March 20 and 21, a Thursday and Friday, plus the following Monday. In that long weekend, they moved with the help of family and friends and set up every classroom. On Monday, the center had its final sanitation inspection and a visit from DCDEE. They opened their doors to children on Tuesday.

The execution of the move, Phillips said, was a miracle in itself. Through the months of ups and downs, she kept thinking of the families she serves and the educators she employs.

“I kept going back to, how do we tell our staff? How do we tell our families? We are in such a child care crisis, there aren’t spots available in many places in the other child cares. How can we disperse 60 children in this county? You know, where are they going to go?”

More on local child care efforts

On the day EdNC visited PlayWorks, Hinson and Phillips were moving in sync. Hinson went between classrooms, providing extra hands for fussy infants. Phillips met with licensing officials in the office during their second DCDEE check-in, which required a fire drill.

“We never really dreamed that something like this would happen,” Phillips said. “We’re just the proud recipients.”

The day before, they had celebrated the team’s accomplishments with a ribbon-cutting ceremony, during which church leaders called the moment “a revival.” But the next day, it was back to the work they both love and are challenged by.

The new space will allow PlayWorks to expand from serving 55 to 88 children as they add three new classrooms (for infants, toddlers, and 4-year-olds) in the coming months.

The church is providing the space at less than $6 per square foot, Cox said, compared with the area’s average commercial lease of $28 per square foot. It is also covering utility costs.

Phillips said they do not expect any problem filling the new seats. They will first check with families on their waiting list. An interested family was visiting the program during the fire drill, during which all children were walked or rolled to a gazebo in the parking lot.

“Word of mouth is just really getting around,” she said.

Valuing educators

Phillips and Hinson are still hiring and rearranging teachers to staff the new classrooms. Each room has three teachers for now, for “an extra layer of quality.”

They start teachers, depending on education level and experience, at anywhere from $10 to $15 per hour. The median wage for the state’s child care teachers was $12.31 in 2022. Though PlayWorks is not immune to the staffing challenges experienced by the field, multiple teachers have stayed for several years.

Teacher Rachel Brionez has worked at PlayWorks since it opened because of “the environment that Sharon and Katie have created” among the staff, the families, and the children. Educators refer to Phillips and Hinson as “the dynamic duo.”

“They value us, and that makes coming to work so much better,” Brionez said. “You don’t dread the alarm clock going off.”

Brionez said her experiences in child care have not always been positive. Phillips said the same about her early career experiences.

Because of the low pay, high stress, and instability, Phillips had discouraged Hinson from going into the field. She pushed her to be a nurse instead. That all changed after one conversation, while Hinson, a high schooler at the time, was helping her mother with her pre-K class.

“She just broke down in tears, and she says, ‘I’m not going to be a nurse,’” Phillips said. “We both cried. And she said, ‘This is all I know through you.’ … I told her, ‘We will do something for your career.’ And that’s why we’re here.”

‘A slim margin’

Because of temporary state funding, the funding cliff that worried providers like Phillips and Hinson in 2023 was pushed back. In March 2025, programs received their final installment of the compensation grant, which has helped them raise teacher pay and plug the gap between what families can afford and what it costs to provide high-quality care.

“With the stabilization grant money from the state, we were able to give teachers those raises and bonuses, and we’re going to do all we can for that to continue,” Hinson said.

Advocates and DCDEE are asking the state legislature this session for child care investments to support the state’s child care subsidy program, which helps working low-income families afford care, and the early childhood workforce. None of the current proposals would provide the level of funding providers were receiving from stabilization grants.

More on child care this session

“It’s worrisome,” Phillips said. “I really put it on the back burner, just knowing that, with the move and everything, we’ve got to move forward.”

As Phillips and Hinson both breathe a sigh of relief, they know their future remains unclear.

“We’ll make it on a slim margin — or I hope we will,” Phillips said. “I’m just thinking very optimistically that we’ll make it work, but it’s going to be very hard.”

A win-win model

Shepherd said the mutually beneficial partnership required resources that not every community has. She sees the state playing an important role in providing grant money to repurpose space — similar to the Rural Downtown Economic Development Grants.

“I just think this is a great model for a lot of places to look at underutilized space and how to bring in some revenue for both,” she said.

Maberry is hoping to find a new way to continue the work of the Ormond Center, which had 55 relationships with churches. Some were working on child care projects, he said. Others were opening mental health services and helping their communities with affordable housing.

“Churches are at their best when they are meaningfully integrated into their community and are making their communities better places to be and to live,” he said.

The Wilkesboro project is an example of the power of dynamic partnerships and possibility in a time of disruption.

“For the church, it’s energized them,” he said. “Like they’ve got kids in their building now, all day, every day, and they’re starting to think, like, OK, well, if we can do this, what else can we do? Imagination can be contagious.”

The children, staff, and administrators at PlayWorks are settling in. Across the street is an assisted living center whose residents can now see playing children on their walks.

Phillips said she does not know whether Hinson will ever let her retire. They both said the new space feels like home.

“With some hard work and perseverance, we’ve made it,” Phillips said.