The Clara Hearne Pre-K Center sits in the middle of a city block, surrounded by tidy single-story homes half a mile from the main drag in Roanoke Rapids. The building has been there for 90 years.

If Clara Hearne — as the locals call the center — was a great-grandmother to the students inside, neighbors might say she looked good for her age. Never mind the flaking paint above the windows, or the patches of mismatched bricks; it’s impressive enough she’s still standing, stoic and solid on her block.

But through her doors it’s a different world.

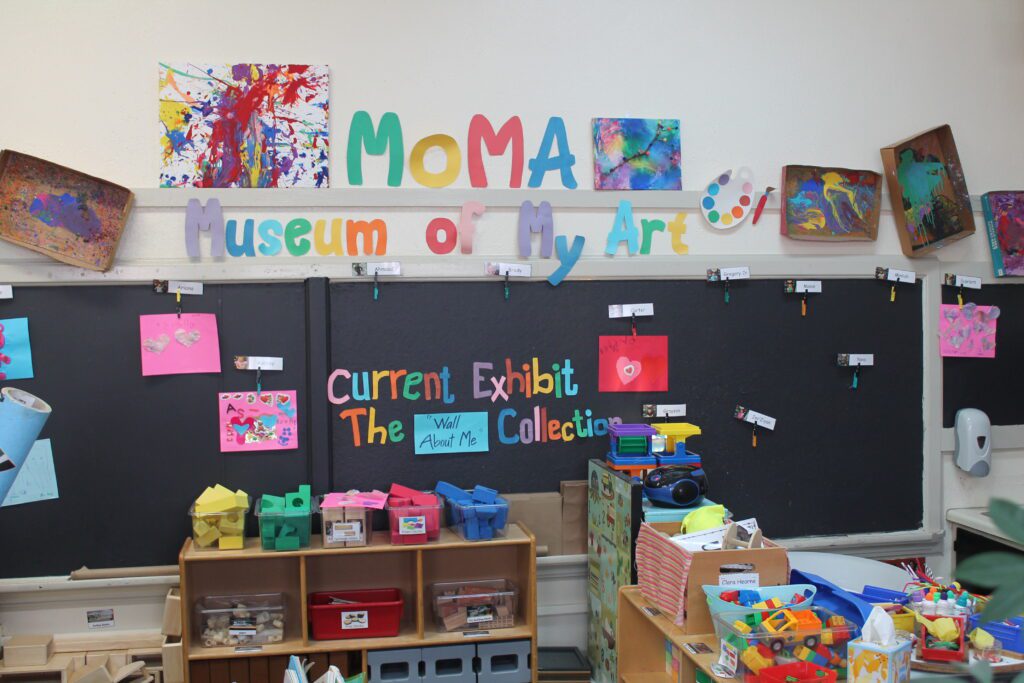

Colorful posters and art, banners and signs abound. The sounds of 4-year-olds bounce down the hall. Plants and lamps and supplies cover every surface. It’s giving warmth and welcome, joy and coziness, right up to the edge of overwhelm.

And the word is getting out.

A group of educators from Elizabeth City-Pasquotank Public Schools (ECPPS) recently visited the site to get inspiration for their own early childhood center and described the students as “thriving.” A team from Northampton County is scheduled to visit next.

In Clara Hearne’s 10 preschool classrooms funded by NC Pre-K, Head Start, Title I, and other local sources, educators work hard to create those thriving conditions. One way they do it is by refusing to suspend or expel students who exhibit challenging behaviors.

Practicing Conscious Discipline

Shelley Williams is determined to keep Clara Hearne’s students from being kicked out of their classes or the school. Williams expressed that commitment on the morning of my recent visit, shortly after one student had slapped her.

“I can’t send them home,” Williams said. “Because it is our job to teach them… If we don’t teach them how to behave when they’re in preschool, it’s not going to happen… So if I keep sending them home, then they’ve not learned anything.”

As director of the pre-k center, Williams has embraced a behavior management model called Conscious Discipline.

Conscious Discipline is an adult-centered approach to supporting students’ healthy emotional regulation. The underlying principle is that if teachers learn to regulate their own emotional responses — especially to challenging behaviors — they’ll be better able to model and teach the social and emotional skills students require.

And that keeps students from being kicked out of their learning environments.

Conscious Discipline says: If a child doesn’t know how to read, you teach them their letters and their sounds. If they don’t know how to do math, you sit down with them and you teach them how to add. But when they don’t know how to behave, you send them home?… So if you’re going to remediate reading and you’re going to remediate math, then why wouldn’t you remediate behavior too? Why are we punishing because they can’t do behavior, but we’re not punishing because they can’t do math, or they can’t do reading?

Shelley Williams

Williams is implementing Conscious Discipline with the full support of Roanoke Rapids Graded School District’s (RRGSD) superintendent, Julie Thompson.

“Traditionally speaking, we taught reading and writing, and we punished behaviors,” Thompson said. She wants to focus more on teaching students the behaviors the district wants, so they can focus less on managing the ones they don’t.

“Who are suspensions for anyway? Are they really to teach the kid?” Thompson said.

This summer, the district’s elementary school administrators will be trained in Conscious Discipline, as Thompson looks to expand the behavior management strategy to additional schools.

Avoiding exclusionary discipline

As EdNC has reported, pre-k suspensions and expulsions can have dire effects — but we don’t know how common they are due to incomplete official data.

What we do know is that suspensions, expulsions, and other forms of exclusionary discipline are applied disproportionately to students of color, which can increase the likelihood of future incarceration.

Letha Muhammad, co-executive director of the Education Justice Alliance (EJA), recalled seeing this firsthand when she was volunteering more than a decade ago at her daughter’s elementary school in Wake County.

“Black boys don’t get a chance, they don’t get to fidget on the carpet the way their white counterparts do,” Muhammad said. “They actually gotta go sit in that corner, in that chair, or they have to be sent out of the classroom… because somehow their behavior is more egregious than their white counterpart.”

Now she leads EJA with a mission to dismantle the school-to-prison and school-to-deportation pipelines. That mission includes preschools, where developmentally appropriate behaviors — like fidgeting during circle time — can result in exclusionary discipline.

“Some people think it’s OK that we push children out of learning environments because they’re acting like children,” Muhammad said.

All young people have the right to, and access to, education in our country, right? And we know that research tells us that the earlier you can get a young child into a formal education program, the better the outcomes are for those young people. And they’re oftentimes displaying age-appropriate behavior at 3 or 4 years old. And so the idea that we penalize or punish them, as opposed to using methods to actually teach them another way, is mind-boggling to me.

Letha Muhammad

Early childhood educators do face some genuinely challenging behaviors. Williams pointed to hitting and kicking as examples — behaviors that are common among young children, but challenging in a learning environment.

She gave the example of the student who had slapped her that morning.

As soon as it happened, Williams asked the student to look at her face and describe it. The student told her it was red and that she looked sad. She affirmed the student’s observation and said she was in pain from the student’s behavior.

Because Williams and her team had used this strategy with the student for previous hitting behavior, the student was able to make the connection between action and consequences — hitting someone when you’re feeling frustrated causes that person to feel hurt and sad.

The student expressed sadness and regret over causing Williams harm and offered an unprompted apology.

“So you have these tough kids, and what is developmentally appropriate is to not send them home,” Williams said. “It’s not in my heart to do that. I feel like we need to fix what’s broken.”

Developing strong relationships between educators and parents is a crucial part of that repair process.

“When we talk about something like suspensions or expulsions, it oftentimes feels very isolating,” Muhammad said. “And as a parent, you’re like: Where did I go wrong? What did I do? How could I? Where did I fail my child? What’s wrong with my child?”

This can lead to parents blaming themselves for what in reality are systemic inequities in the application of exclusionary discipline. Williams and the educators at Clara Hearne work closely with parents. She sees it as one of their strengths.

“I feel like we are not judgmental,” Williams said. “I feel like parents can come in here and just spill the beans, like they tell us everything… maybe it’s just the aura that’s here, I don’t know.”

There are parents out here who want different outcomes for their students. They want their children to be able to thrive. And I want policymakers to be open to hearing the experiences, stories, and recommendations of those parents.

Letha Muhammad

Williams shared the story of a student who had been kicked out of several other early care and learning centers. When Williams reached out to the student’s parent to discuss a challenging behavior, the parent assumed the student would be kicked out, and was surprised when Williams told them they’d just “regroup tomorrow.”

“I’m not kicking (them) out,” Williams told the parent. Because she knows removing young students from their learning environments at this stage in their development can have devastating effects.

“They don’t get the foundational grounding knowledge that they need to then go into kindergarten and be successful,” Muhammad said. “It also could have a psychological impact on a 4-year-old… It’s essentially, you can throw me away, I’m not worthy of being able to stay in this place.”

Building relationships with parents of preschoolers, rather than suspending or expelling their children, is part of what helps prepare students and their families for entering the K-12 system.

“We may not have taught them their ABCs, but we taught them how to not hit their friends, how to wait, all the things that you have to do as precursors to education,” Williams said.

“The more skills they get here, the better they are as they transition to kindergarten,” Superintendent Thompson said.

Imagining alternatives

The educators at Clara Hearne still have more they want to do. So does the superintendent.

“I wish one day we could get the grant to have more spaces,” Thompson said, referencing her district’s multiple attempts over the last few years to secure funding for a new, larger center. The designs for the new building are complete and there are students on the waitlist, ready to fill classrooms if and when the project gets funded.

Williams is focused on making sure that Conscious Discipline is being adopted with fidelity by all 20 teachers and teaching assistants in all 10 of her existing school’s classrooms. And she’s thinking about new ways to support those teachers too, especially on harder days.

“I think that having an end-of-the-day debrief would be fabulous,” Williams said.

RRGSD already has some experience doing that — in a different context.

When a student suffered a sudden cardiac arrest during recess and died three years ago, the district brought together teachers, staff, and emergency responders who were directly affected to process the trauma of that experience together, and better support the students in their care.

This type of adult-centered approach — giving parents, families, and educators the tools they need to appropriately support children — is what Muhammad imagines for our public education system statewide.

“It’s really like a community model that is providing all of the needs for that particular place so that young children get to thrive, so that we don’t throw them away and give up on them before they even get started,” Muhammad said.