by Katie Dukes and Liz Bell, EducationNC

January 23, 2025

Policymakers across the political spectrum ran for office on child care issues in 2024. From the presidential campaigns to local races, Democrats and Republicans both acknowledged that our early care and learning systems are not functioning for families, educators, or their communities.

“You have to be willing to think about the work differently, and to use a phrase that my progressive friends like to use when they”re speaking about the people they’re trying to serve: You have to meet people where they are,” said Shannon Jones, a former Republican state representative and senator in Ohio, and founder of Groundwork Ohio, a policy and advocacy organization for young children. “That same thinking must be applied to the people you’re trying to convince to vote for this.”

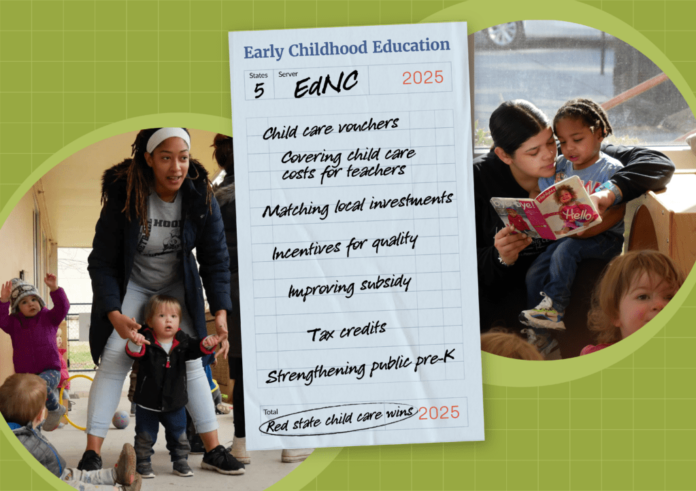

EdNC’s early childhood team met with folks working on behalf of child and family freedom and well-being in five red states — Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Ohio — to learn which policies have earned cross-partisan support and could be a good fit for North Carolina’s early care and learning landscape. Here’s what we learned.

Child care vouchers

Much like North Carolina, Ohio has been offering families publicly-funded vouchers to pay for private school for decades. Lawmakers in Ohio in recent years have lifted income caps on those vouchers, along with their requirement that to be eligible, families must live in an area with schools designated as “failing.”

“It has resulted in more than a billion dollars leaving the public school system and actually not serving additional kids in private schools,” Jones said. “It’s just serving the same kids in the private schools whose parents are higher incomes and who had already chosen to send their kids there.” That “has caused a lot of anxiety among traditional public school advocates, and a lot of anxiety with progressives and Democrats who just really oppose this.”

That might sound familiar to North Carolinians who have been following the recent expansion of our state’s “Opportunity Scholarships.”

Jones and others saw an opportunity to apply the principle behind school vouchers — giving families the freedom to choose an educational setting for their children regardless of affordability — to early care and learning.

Ohio’s Child Care Choice Program is a voucher program for families with incomes between 146% and 200% of the federal poverty level. The new voucher is built on top of the existing application and payment infrastructure, so families who apply for Ohio’s Publicly Funded Child Care (PFCC) but are over the 145% income threshold are automatically considered for vouchers. If approved, they can choose a licensed child care program, and the cost of tuition will be fully or partially covered by the voucher and paid to the child care program on their behalf.

Since the program came into effect in April 2024 under Republican Gov. Mike DeWine, thousands of new children and families have enrolled in licensed child care across the state.

“We were able to get more families and children access to quality early learning, while supporting families to get back into the workforce, providing that economic benefit and the need that businesses in our community have,” Jones said. “And we’ve done it in a way that is consistent with the voucher program that [Republicans] love in the K-12 system.”

Reducing child care costs for teachers

As in other states, Kentucky child care programs were “hanging on by their fingernails” through and after the pandemic, said Andrea Day, director of the Division of Child Care in the state’s Cabinet of Health and Family Services. Providers couldn’t increase compensation to attract and retain qualified teachers. Classrooms were closing.

In 2022, the state division got creative. With the knowledge that many child care teachers were also parents of young children, Kentucky became the first state to subsidize child care costs for child care teachers regardless of their income.

This was done through the state’s Child Care Assistance Program, which helps low-income families with child care costs.

In Kentucky, families must make no more than 85% of the state’s median income to qualify. There are some exceptions to these income requirements. For example, if parents receive payments for fostering children, they do not have to include those funds in their income calculation.

The state division decided to use federal money from the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) to add income made through working in licensed child care as another exception. Teachers who work 20 hours or more per week in family child care homes or centers were included. Day said the policy provided “a recruitment and retention tool that was not on the backs of providers.”

In 2023, 3,200 parents were employed in early care and education, and 5,600 children had benefited from the program, Day said. It put money back into the pockets of parents, who were struggling with high costs of care, and providers, who were often paying for employee discounts.

About a dozen states have passed similar legislation or are considering it, including Arkansas, Oklahoma, Nebraska, Arizona, and Iowa, according to the Alliance for Early Success.

In 2024, this was one of several pandemic-era investments that the state was able to continue funding when ARPA money ran out. The state passed House Bill 6, which included a $60 million child care investment. The legislation is the first of its kind in the state’s history, Day said. It includes $26.25 million in state funds over two years to continue helping child care teachers with child care costs.

Sen. Danny Carroll, a Republican, was a key advocate, Day said. With experience as owner of Easterseals West Kentucky Child Development Center, he explained the broken business model of child care to fellow legislators.

“We can’t simply increase the cost of the product, because not only do our subsidy kids suffer, but our private-pay families shoulder the greater burden, because they’re getting no assistance,” Day said.

State match to local investments

A partnership between local and state government — with revenue from “sin taxes” like those on gambling — is expanding access to child care for those who need the most help.

The Louisiana legislature established an Early Childhood Education Fund in 2017 with the goal of incentivizing localities to raise funding to expand child care access by matching local funds at a 2:1 rate. For every two dollars a parish would generate, the state would add one dollar.

The law requires the local and state funds to be spent on child care programs serving low-income families, and programs offering care to the youngest children — the hardest to find and most expensive across the country.

Before the state placed any money in the fund, New Orleans got busy. In 2017, the city made a $750,000 early childhood investment. By the time 2019 rolled around, the state allocated its first dollars into the fund, and began matching local funds dollar for dollar.

Meanwhile, legislators had begun discussing the possibility of placing sports betting in front of voters. Child care advocates saw an opportunity for untapped revenue they needed in order for the state to match localities’ investments. Other parishes were quickly following New Orleans’ lead, said Libbie Sonnier, executive director of the nonprofit Louisiana Policy Institute for Children.

“They really used early childhood education as the shiny, pretty thing to get the legislators to vote to say, ‘Let’s bring this to the people,’” Sonnier said.

The ballot initiative passed. And New Orleans kept leading the way. Its $750,000 grew to $1 million, then $3 million. In 2022, New Orleans voters passed a local property tax to generate $21 million per year for child care for infants through 3-year-olds.

“Since New Orleans, then we’ve had like 13 other local parishes (that) have said we want to get in the game,” Sonnier said.

The governor tapped into leftover K-12 funds to match New Orleans’ recent large investments. Now the local investments total about $30 million, Sonnier said.

“What we’re facing right now is, in probably a year or two, the need is going to outpace what’s in the fund,” Sonnier said.

A state task force is discussing a sustainable early childhood funding formula that guarantees consistent funding for families and children, creates opportunities across parishes, and does not discourage wealthier localities from going big.

Incentives for quality improvements

A partnership between Alabama’s Department of Human Services (DHS) and Department of Early Childhood Education (DECE) has produced meaningful child care quality improvements over the last three years.

For context, the federal government created incentives for high quality in child care programs by requiring states that receive federal child care subsidies to spend some portion of the funds on improving quality. One way of doing that is by implementing a Quality Rating and Improvement System (QRIS). Both Alabama and North Carolina use scales of one to five stars to demonstrate quality through their QRIS.

In North Carolina, QRIS is intertwined with our child care licensing program, meaning that each licensed site is rated on the five-star scale. And in both North Carolina and Alabama, higher star ratings make programs eligible for higher rates of subsidy reimbursement.

But participation in the QRIS scale in Alabama is voluntary for licensed child care programs, and that was limiting the state’s ability to measure quality and demonstrate improvement — until 2022.

That’s when early childhood leaders implemented a plan to use both state and federal dollars to not only incentivize participation in its QRIS, but improvement on the five-star scale.

Faye Nelson, deputy commissioner for DHS, told EdNC there were just a handful of five-star programs before the expansion of Alabama’s quality incentive program. Now there are 85 — more than a quarter of all QRIS participants.

Here’s how it works: All licensed child care programs are automatically eligible for one star. When they opt in to QRIS, they get the one-star rating and the annual incentive payment that comes with it. Programs are also eligible to receive technical assistance to increase their star ratings.

Those annual incentive payments range from $2,200 per year for a small family child care home with one star, to $81,000 per year for a large child care center with five stars.

“So this is what we brought before our legislators to say, we need you all to support this, because this is the result of what has happened with us utilizing these federal dollars to incentivize quality-rated programs,” Nelson said. “And we know that every parent … you want your children in quality-rated programs.”

Improving child care subsidy

As states further understand the importance of child care for their economic well-being, they are investing in child care assistance for working parents.

Child care subsidy is the largest federal source of child care funding, and it’s aimed at helping working low-income families afford child care. States also provide matching funds and general appropriations from their budgets.

But the program does not meet the need or cover the full cost of care. About 13% of children who qualified for assistance were accessing the program in 2021. And both parents and child care providers pick up where the program leaves off.

The pandemic’s federal relief funding created opportunities for many states to expand the reach of their subsidy programs or boost the assistance for participating parents and programs. Some states have continued those efforts with state appropriations.

In Florida, the legislature last year invested $46 million to increase the rates that providers receive to participate in the program and changed the rate calculations to lower disparities from county to county.

The state is also looking at its subsidy program every year to ensure rates are staying in line with the market as well as the estimated cost of quality, said Molly Grant, executive director of the Association of Early Learning Coalitions.

Multiple advocacy organizations are pushing to increase the eligibility threshold for the program (now 150% of the federal poverty line) in the next year. Grant said the argument is simple: “Parents can’t go to work if their kids can’t go to school.”

In Kentucky, last year’s House Bill 6 continued multiple subsidy expansions that were first tied to ARPA funding, including nearly doubling the rates providers receive in the program. Along with covering child care teachers’ child care costs, the legislation continued transitional child care, which covers half of a family’s subsidy payment for six months after they lose eligibility.

And in Ohio, advocates have moved the eligibility from 130% of the federal poverty line to 145%, with a goal of reaching 200% through the voucher program established by the governor.

North Carolina has recently made similar investments. In 2023, legislators allocated an additional $75 million in recurring funding in Senate Bill 20 to increase the amount participating child care providers were receiving. Advocates are rallying behind a floor rate this year so that the amount providers receive does not fluctuate so widely from county to county.

Tax credits

Since 2007, Louisiana has been a leader in early childhood financing through a series of child care tax credits for families, child care providers, teachers and administrators, and businesses.

Known as the “School Readiness Tax Credits,” the five programs have helped increase the quality of care, rewarded early childhood educators for increasing their education, provided relief to families paying high child care costs, and increased businesses’ awareness and support of child care for their employees.

“Early childhood education is tax policy,” said Sonnier, executive director of the Louisiana Policy Institute for Children. “If people think it’s not, then they’re not playing in the right sandbox.”

The five credits in the package are:

- Child Care Provider Credit, which sends an annual $750 to $1,500 per child to programs who have earned at least two stars in the state’s accountability system. The amount depends on the program’s quality rating.

- Child Care Teacher and Director Credit, which in 2023 was worth between $2,000 to $4,000 depending on the educational level attained through the Louisiana Pathways Child Care Career Development System.

- Child Care Expense Credit, which gives credits to parents with children enrolled at a facility with at least two stars in the rating system. The amount depends on the program’s quality rating and the family’s income.

- Business-Supported Credit, which covers between 5% and 20% of expenses, depending on the program’s quality rating, related to supporting child care, like renovating or building a facility or subsidizing employees’ care costs.

- Child Care Resource and Referral (CCR&R) Agency Credit, which provides a 1:1 match up to $5,000 per year to businesses who donate to CCR&Rs, organizations that support families and child care providers.

Florida also recently passed a child care tax credit program. Last year the legislature allocated $5 million to provide credits to businesses that support the child care needs of their employees through on-site care or subsidizing employees’ care. It helps cover initial start-up costs, as well as reimbursement for each supported child.

Grant said advocates will focus next on making the program more accessible to small businesses.

“It’s meant to try and engage businesses in investing into this space as well, and get them engaged in the conversation,” she said. “… Hopefully we’ll see that entire $5 million used up this year.”

Strengthening public pre-K

The National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) has been publishing annual State of Preschool reports for more than two decades, and for each of the last 18 years, Alabama’s universal public preschool program has achieved the highest possible quality rating.

North Carolina hasn’t met that level of quality since 2015, despite having half the enrollment rate of Alabama due to income eligibility requirements, insufficient funding, and workforce limitations.

Jan Hume, acting secretary of Alabama’s Department of Early Childhood Education, told EdNC that much of the success of Alabama’s First Class Pre-K (FCPK) has had to do with developing the state’s early care and learning workforce over time.

“We didn’t want to do it overnight,” Hume said. When you move too quickly “you lose quality because you don’t have the workforce. And so we really tried to make sure that we built a plan and that we could also build the workforce to go along with it.”

Alabama’s Department of Early Childhood Education has created pathways to support educators earning credentials that meet NIEER’s high quality standards, in addition to requiring pay parity with K-12 teachers regardless of whether classrooms are operated by school districts, private child care centers, community organizations, or Head Start programs.

NC Pre-K has a similar mixed-delivery system, but does not require pay parity.

Alabama is also part of a national initiative aimed at increasing the inclusion of home-based child care programs in state pre-K systems. (In North Carolina, Durham’s local pre-k program is also part of this cohort.)

“In places like this where we’re so rural, there’s not going to be child care centers within driving distance for a lot of families,” Hume said. “And we’re seeing more families choose smaller settings for their children. And so if we’re going to really expand pre-K to meet all the needs, we’ve got to figure that piece out.”

Alabama has the flexibility to do so.

“We don’t have a lot of state statutes that govern how we do pre-K,” Hume said. “We’ve had a lot of freedom to really build a system that meets the needs for Alabama families and children, and that’s been wonderful.”

This <a target=”_blank” href=”https://www.ednc.org/01-23-2025-cross-partisan-child-care-red-states-solutions-approaches-models/”>article</a> first appeared on <a target=”_blank” href=”https://www.ednc.org”>EducationNC</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src=”https://www.ednc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/cropped-logo-square-512-150×150.png” style=”width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;”><img id=”republication-tracker-tool-source” src=”https://www.ednc.org/?republication-pixel=true&post=242556″ style=”width:1px;height:1px;”><script> PARSELY = { autotrack: false, onload: function() { PARSELY.beacon.trackPageView({ url: “https://www.ednc.org/01-23-2025-cross-partisan-child-care-red-states-solutions-approaches-models/”, urlref: window.location.href }); } } </script> <script id=”parsely-cfg” src=”//cdn.parsely.com/keys/ednc.org/p.js”></script>