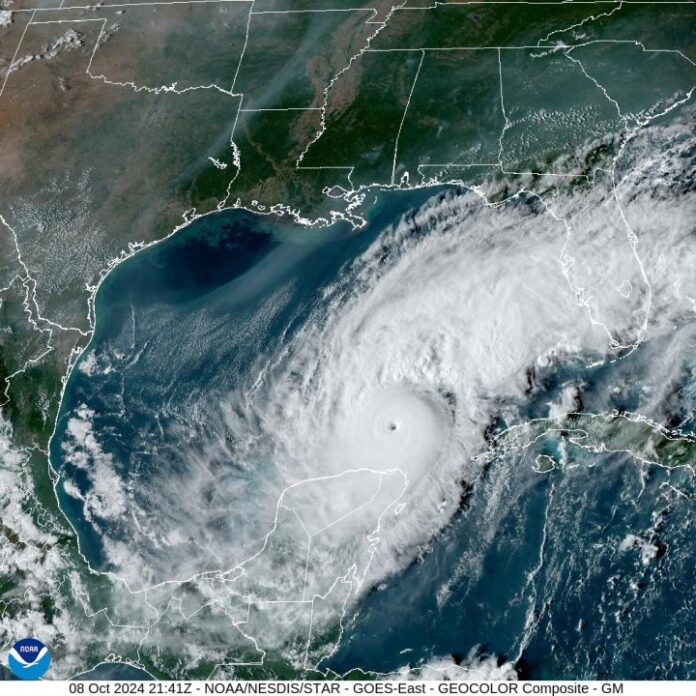

(WGHP) – With Hurricane Milton in the Gulf of Mexico and several southeast cities cleaning up from Helene, meteorologists have been using several key weather terms that can be hard for the average person to understand.

Let’s dive into some of the frequently used words and phrases that are on repeat during this busy week of hurricane season.

Structure of a Hurricane: Eye, Eyewall, Outer Bands

A hurricane is made up of three basic parts: the eye, the eyewall and the outer rain bands.

The eye of a hurricane is the clear and calm central part of a hurricane. It appears like a “hole” towards the center of the storm. The inside of the eye is typically associated with light winds and fair weather.

A small eye typically means the hurricane is stronger. This is because it’s able to rotate around the center point faster.

Think of it like a figure skater who is spinning around. If they bring their arms closer to their body, they’re able to spin faster. The faster a storm can spin around a center point, the stronger the winds with the system can be.

The eyewall of a hurricane is the ring of thunderstorms that surrounds the eye. The eyewall has the strongest winds and the heaviest rain. The eyewall and eye can grow or shrink in size, and, when these changes occur, it can impact the storm’s wind speeds, which is a measure of the storm’s intensity/strength.

We’ll talk more about the changes in size of the eye/eyewall and its impact on the strength of a hurricane in the eyewall replacement cycle section.

The outer bands of a hurricane are basically the rest of the storm. They’re the areas of rain, storms and clouds that are away from the center of the storm and resemble a spiral.

The outer bands are able to produce very heavy bursts of rainfall as well as strong winds and tornadoes. However, sometimes there are breaks between rain bands where no rain may be falling and wind may be lighter.

Maximum Sustained Wind vs. Wind Gust

Maximum sustained wind is the highest steady wind that lasts for at least 20 seconds and is measured at 33 feet above the surface. The maximum sustained wind determines the strength of a hurricane on the Saffir Simpson Scale.

A wind gust is a sudden increase in wind speed that’s at least 10 mph faster than the sustained wind and lasts less than 20 seconds.

Saffir Simpson Scale

The Saffir Simpson Scale is the rating system for hurricanes based on their sustained wind speed.

A Category 1 hurricane has winds of 74 mph to 95 mph.

A Category 2 hurricane has winds of 96 mph to 110 mph.

A Category 3 hurricane has winds of 111 mph to 129 mph.

A Category 4 hurricane has winds of 130 mph to 156 mph.

A Category 5 hurricane has winds of 157+ mph.

Any hurricane with a Category 3 rating or higher is considered a major hurricane.

Cone of Uncertainty

The cone of uncertainty is the name for the forecast path of a hurricane or tropical system issued by the National Hurricane Center.

The cone only shows the most likely path of the center of a hurricane. It does not show the size of a hurricane or how far away from the center effects could reach.

The forecast path shows the track for every 12 hours up to three days before landfall and then 24-hour intervals for five days before landfall.

If the edges of the cone are closer to each other that means forecasters have a higher confidence in the path that the center of the storm will take. Whereas, if the two sides are further apart from each other, that means there’s low confidence in the path.

The cone of uncertainty is updated every six hours by the National Hurricane Center. The updates happen at 5 a.m., 11 a.m., 5 p.m. and 11 p.m. However, updates on the storm’s intensity occur every three hours.

Sea Surface Temperatures

The sea surface temperature is the temperature of the top few feet of the ocean. It’s impacted by the sun, the wind and ocean currents.

Hurricanes require warm ocean waters to develop. Typically, tropical systems require temperatures around 80 degrees or warmer from the surface to 150 feet below.

The warmer the sea surface temperatures and the deeper below the surface those warm temperatures reach, can provide “fuel” in the form of heat and moisture for hurricanes to develop.

Wind Shear

According to the National Weather Service, wind shear is the change in wind speed and direction over a short distance. It has a big impact on hurricanes and tropical systems.

Strong wind shear means there are constant changes in the wind speed and direction in an area. This can essentially “blow” or “tear” a hurricane apart. Weak wind shear is an essential part of the development and survival of a tropical system.

Wind shear impacts the winds in a tropical system and how heat and moisture are transported within the hurricane. This disruption in energy transfer essentially kills a tropical system.

Storm Surge

According to NOAA, storm surge is the abnormal rise in sea level that occurs during a hurricane and is caused by the strong winds pushing the water toward the shore.

Storm surge is measured as the height of the water above the normal tide. The height of storm surge at any location depends on the shape of the coastline, the track of the storm as well as the intensity, size and speed of the storm.

According to FEMA, storm surge has been known to go 25 miles inland, completely submerging cars and flooding houses. In fact, storm surge with Hurricane Ike in 2008 reached 30 miles inland.

If land is below sea level or relatively close to sea level, storm surge can reach further inland.

To calculate what the storm surge could be at your location, you need to know what the forecasted peak storm surge is at sea level from the National Hurricane Center as well as your location’s elevation above sea level. The forecasted peak storm surge at sea level minus your location’s elevation above sea level will equal the forecasted surge at your location.

For example, if the National Hurricane Center is forecasting 8 feet of storm surge at sea level and your house is 4 feet above sea level then the forecasted storm surge at your location would be 4 feet.

Rapid Intensification

Rapid intensification is defined by the National Hurricane Center as an increase in the maximum sustained winds of a tropical system by at least 35 mph in a 24-hour period.

An increase of 35 mph winds would change the strength of a hurricane from one category to the next on the Saffir Simpson Scale.

An example would be if a hurricane had winds of 90 mph and increased to wind speeds of 125 mph. That’s an increase from a category 1 hurricane to a category 3 major hurricane within 24 hours.

Certain conditions are needed for a storm to rapidly intensify. Those conditions include weak wind shear, lots of moisture and warm sea surface temperatures (over 80°).

All of those weather conditions were present when we watched Hurricane Milton rapidly intensify this week.

In fact, Milton rapidly intensified from a category 1 hurricane to a category 5 hurricane in just 18 hours making it the third fastest rapid intensification in the Atlantic behind Wilma (2005) and Felix (2007).

Eyewall Replacement Cycle

In strong tropical systems, the outer rainbands can form an outer ring of thunderstorms that moves inward toward the center, taking away the moisture from the main eyewall of the hurricane and causing the eyewall to “collapse” in on itself.

As this happens, the hurricane is weakening and the new eyewall is “replacing” the original one. Once the replacement has occurred, the storm will then return to its original strength or it can even grow stronger.

This process of a new eyewall forming from outer rainbands coupled with the weakening and restrengthening of a tropical system is known as the eyewall replacement cycle.